41. RECAP: The Fork in the Fourteenth Amendment

How two visions of equality shape every race case today

At first glance, Equal Protection doctrine seems to offer a clear promise: the government must treat people equally. But when it comes to race, that promise divides into two very different visions of what equality really means.

This isn’t just a technical debate. It’s the tension underneath nearly every major Supreme Court case involving race in the last 50 years. And it’s the framework we need if we want to make sense of where Equal Protection law has been—and where it might go.

Two Theories, One Clause

The Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause is famously short:

“No State shall … deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

But courts and scholars have long argued over what that means.

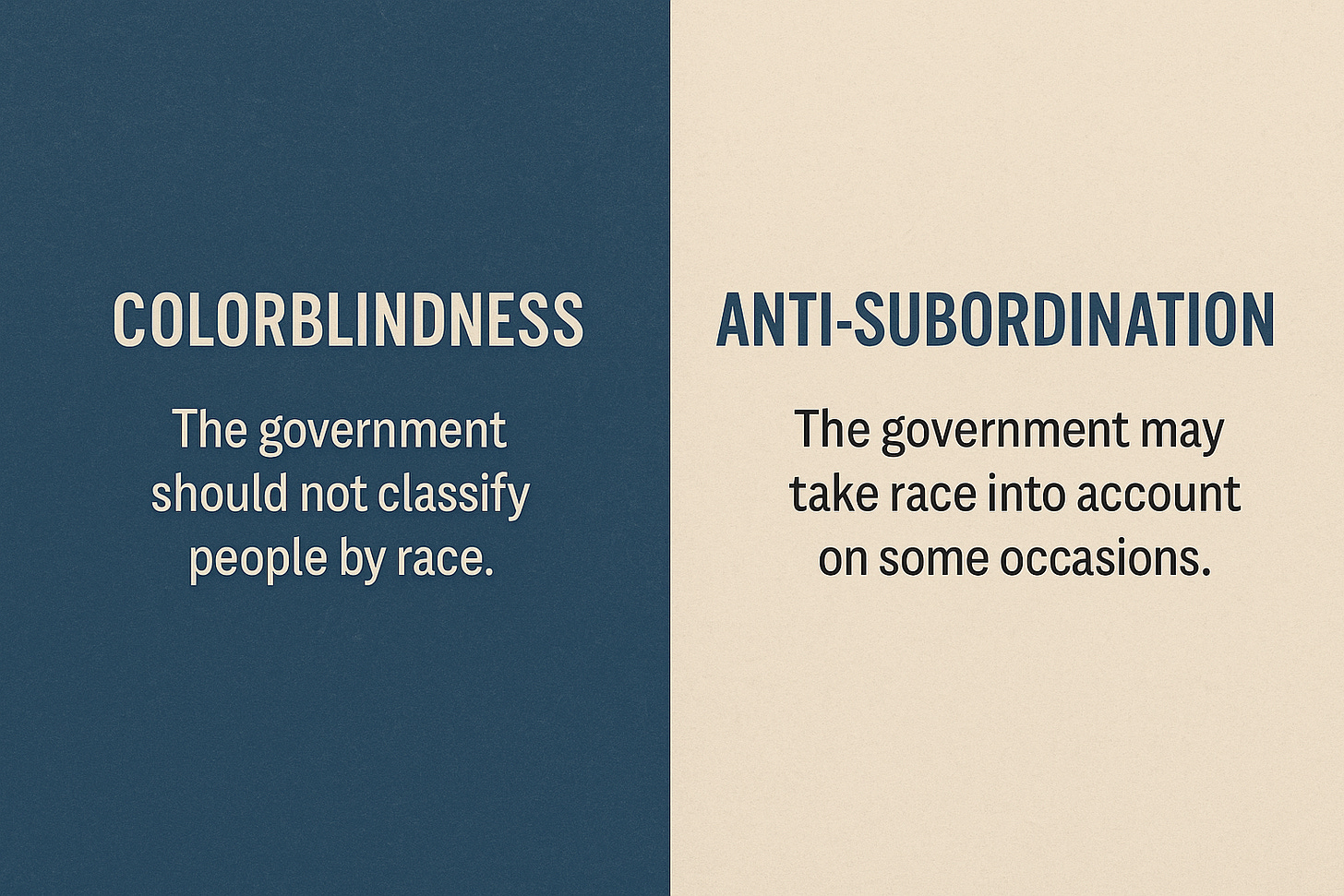

On one side is the idea of colorblindness:

The government should never classify people by race. Not to harm, not to help. Racial neutrality is the goal, and anything that explicitly uses race—even to remedy past injustice—is inherently suspect.

On the other side is anti-subordination theory:

The point of the Fourteenth Amendment wasn’t just to end classification. It was to end racial hierarchy. Under this view, the law can—and sometimes must—take race into account to dismantle systems built on white supremacy and exclusion.

Why This Tension Matters

This isn’t an abstract disagreement. It plays out in real cases, with real stakes:

In affirmative action, colorblindness says: you can’t use race in admissions. Anti-subordination says: race-conscious admissions are necessary to overcome past and ongoing inequality.

In voting rights, colorblindness says: draw districts without regard to race. Anti-subordination says: race must be considered to ensure Black and Latino voters aren’t silenced by gerrymandering.

In criminal justice, colorblindness says: treat everyone equally under the law. Anti-subordination asks: what if facially neutral laws have racially disparate impacts that trace back to systemic bias?

Even in cases that seem unrelated—like school funding, environmental justice, or public health—this tension lurks beneath the surface. Is the role of the law simply to prevent explicit racial discrimination? Or does it have a responsibility to actively correct the long tail of inequality?

Students, Start Here

This isn’t just another debate among theorists. It’s the spine of Equal Protection law.

Every case you’ll read sits on this spectrum. Even when the Court doesn’t say it out loud, it’s choosing a side.

Some justices lean toward a purist colorblindness. Others argue that without a willingness to acknowledge race, we risk entrenching inequality under the guise of neutrality.

The Risk of Forgetting History

One of the most powerful critiques of colorblindness is that it forgets the historical context in which race-based laws emerged. It flattens laws designed to perpetuate white supremacy and laws designed to remedy it into the same category: “racial classification.” But context matters. Motive matters. Power matters.

Anti-subordination theorists remind us: if you treat all racial classifications the same, you erase the very history that made the Equal Protection Clause necessary in the first place.

The Court Today

In recent decades, the Supreme Court has moved steadily toward a colorblind framework. Strict scrutiny now applies across the board, no matter the purpose behind the racial classification.

But the doctrine is not settled. The tension remains. And each new case becomes a battleground for which vision of equality will prevail.

Final Thought

When trying to make sense of modern Equal Protection law, start here:

Does this case treat race as a problem to be ignored—or a legacy to be addressed?

Because the Constitution may promise equal protection to all. But how we understand equality changes everything.

As I read this article, the reminder that “context matters” resonated strongly with me. This highlights that the law should not be divorced from the historical conditions and inequalities it was designed to confront.

Through the lens of “colorblindness” treating all racial classifications the same risks ignoring the structural and historical realities that still shape people’s lives today. This tension makes Equal Protection doctrine feel less like a neutral set of rules and more like an ongoing negotiation over whose vision of justice the Constitution should embody.

Through the lens of “anti-subordination” considerable risks are involved in implementing a pick-and-choose application of race across a variety of issues. This could open a floodgate of issues in determining when its use is appropriate.

Ultimately, if the Court increasingly embraces one view over the other, I would argue that decided interpretation risks turning the Equal Protection Clause into a tool that may further entrench inequality rather than dismantles it.

I feel like colorblindness is the most practical stance for the law to take, as the anti-subordination stance lends itself to endless debate about when and how the government should take race into account. Who would make those decisions and under what standards? What exactly would constitute a suitable remedy for past injustices? Not that I disagree with the purpose of the anti-subordination stance, just that it would create never-ending causes to question and potentially litigate government decisions.