32. Crisis, Coercion, and Constitutional Meaning

What the Fourteenth Amendment tells us about today's battles

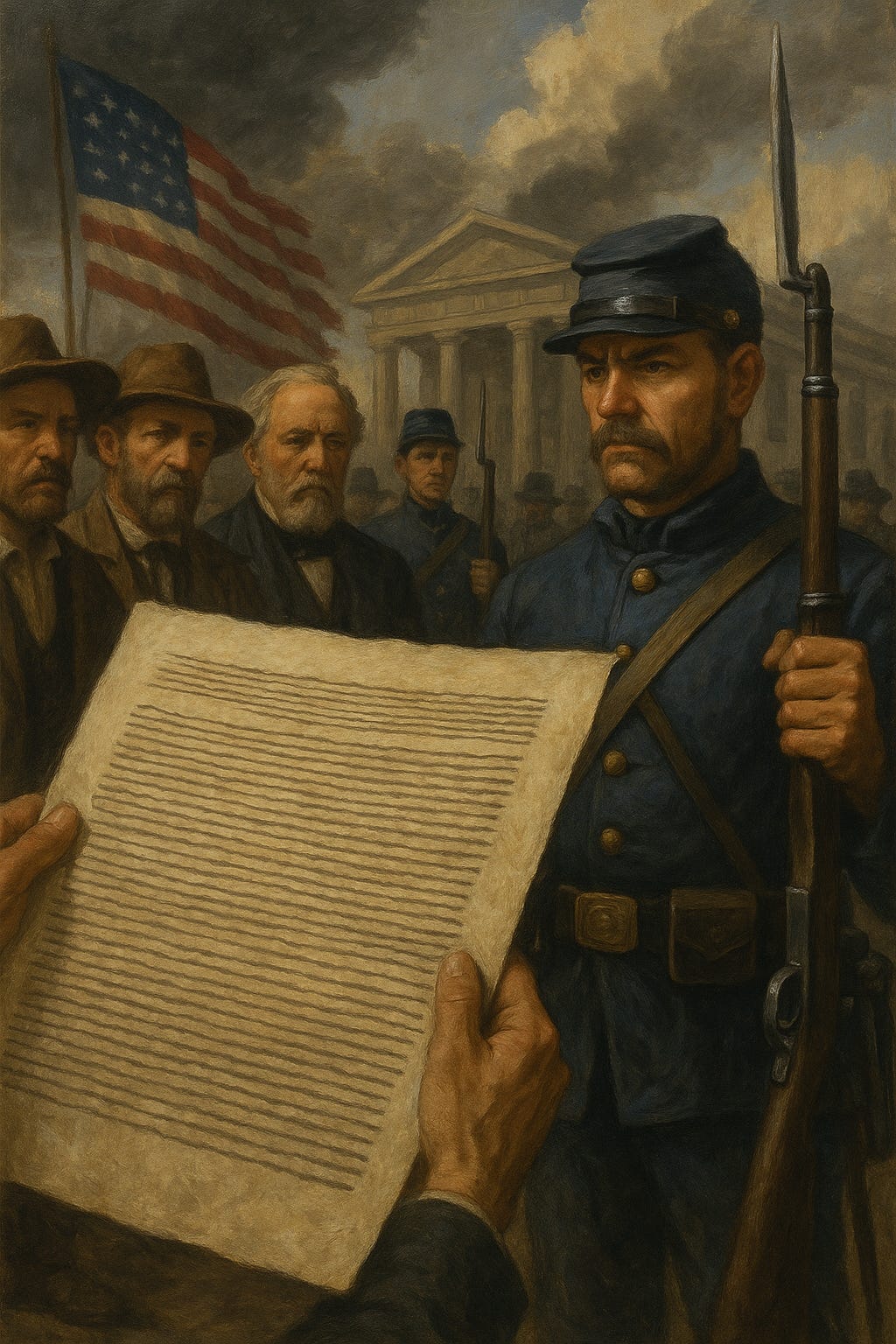

The Fourteenth Amendment is the backbone of modern constitutional rights, but its origins were anything but clean. Passed after the Civil War, under military occupation, and as a condition for Southern states to rejoin the Union, the amendment’s ratification looked more like political hardball than democratic consensus.

Critics, then and now, have called it coercion. A Constitution revised at gunpoint.

But this history is especially relevant today, as we find ourselves asking:

What makes a constitutional provision legitimate?

Is it how it was adopted? Who agreed to it? Or is legitimacy something that builds over time—through practice, precedent, and public acceptance?

Originalism vs. Living Constitutionalism

This tension lies at the heart of today’s most polarizing constitutional debates. Justice Thomas, for example, has argued that we should revive the long-dormant Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. But to do so, he insists, we must be faithful to its original meaning (as understood in 1868).

That’s a bold move. But it raises an ironic dilemma: If you’re demanding strict historical fidelity, what do you do with a clause born out of political coercion? Can something ratified under pressure serve as a rigid constraint on modern rights?

The deeper question is: Does legitimacy come from original consent, or from what we’ve done with the text since?

Dobbs, Obergefell, and the Politics of Precedent

We’re living through a period of retrenchment. Dobbs overturned Roe, rejecting 50 years of precedent. Conservative justices argued that the right to abortion had no historical grounding. Others fear that Obergefell, which recognized same-sex marriage, could be next.

These decisions turn heavily on the idea that rights must be “deeply rooted in history and tradition.” But whose history? Whose tradition? If a right emerged after long exclusion, does that make it less valid—or more necessary?

The Fourteenth Amendment’s own story complicates any tidy answer. It wasn’t born of national consensus. It was born of a crisis, a moment when the ordinary political process had failed, and more forceful intervention was required to reimagine citizenship and equality.

That’s why it’s so hard to separate constitutional meaning from political context. Many of the rights we debate today—bodily autonomy, family recognition, equal treatment under the law—trace back to a provision forged under duress, but reaffirmed over generations.

Judicial Power and Public Trust

The legitimacy questions don’t stop at rights. They extend to the courts themselves. As the Supreme Court grows more assertive in reshaping constitutional law, many Americans are asking:

Who gave them the authority to make these decisions?

Can unelected judges overturn rights that millions have come to rely on?

If the Court no longer reflects the political will of the country, is its power still legitimate?

Again, the Fourteenth Amendment offers perspective. Its passage was top-down. But its endurance has been bottom-up: reaffirmed by courts, by movements, by democratic struggles. Its authority today doesn't come from how it was passed, but from the constitutional culture we’ve built around it.

Why It Matters

In the end, the Fourteenth Amendment reminds us that constitutional legitimacy is a living thing. It doesn’t always start with consensus. Sometimes it starts with rupture, with someone drawing a line and saying: From now on, this is the law.

The real test is what we do with that law over time. Do we narrow it, hollow it out, return it to its original limitations? Or do we let it grow into something that reflects who we are now, and not just who we were then?