1. Staring Into the Constitutional Abyss: Why Words Matter

Ruminations on starting with the text itself

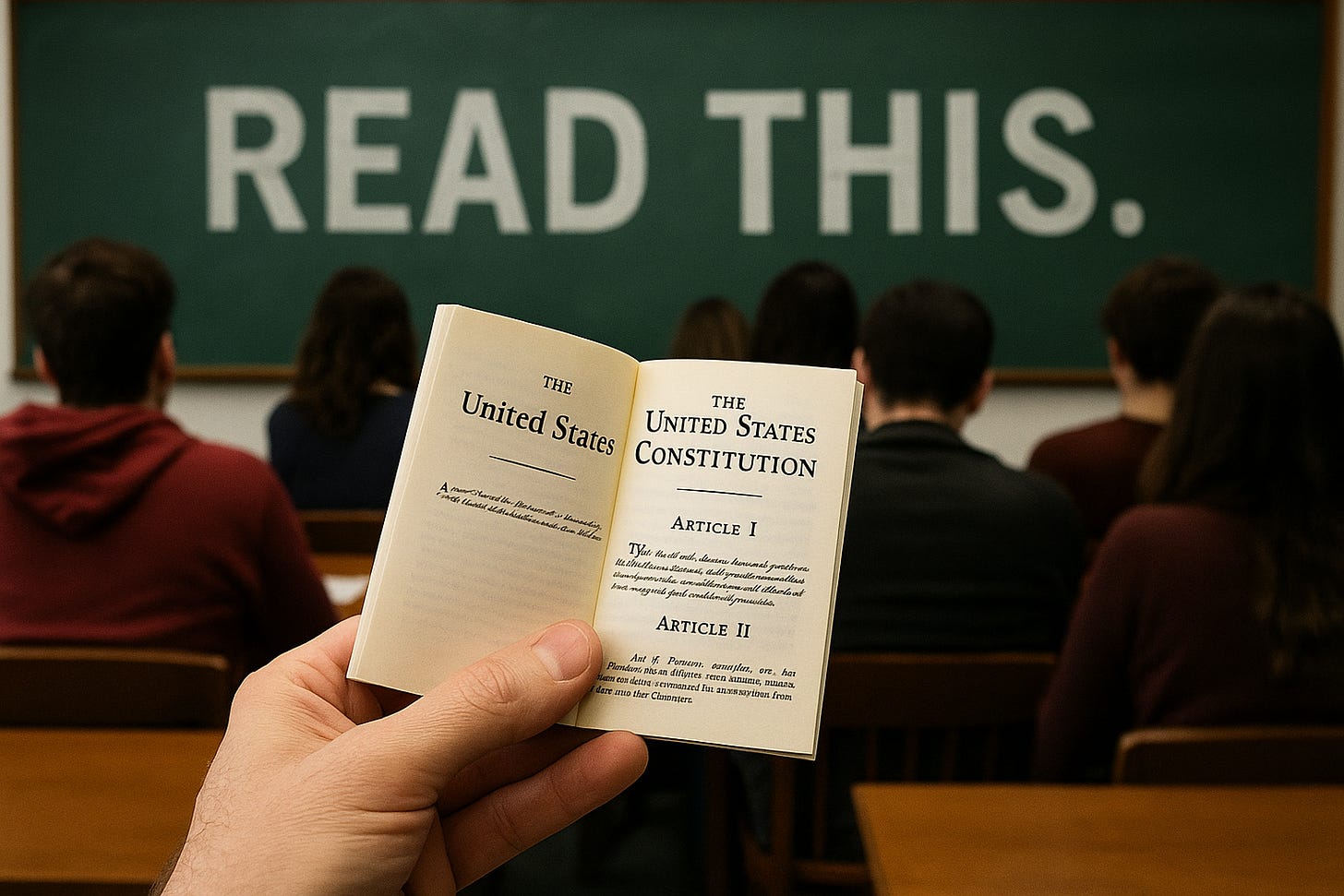

There’s something beautifully absurd about handing a room full of law students the Constitution and saying, “Read this.” It’s like asking someone to read the Torah without commentary, the Bible without interpretation, or the Qur’an without scholarly guidance. You watch their faces as they encounter phrases like “privileges or immunities” and “due process” for the first time—words that have launched a thousand law review articles and at least as many heated Supreme Court dissents.

The Power of Plain Reading

Religious scholars know the importance of reading sacred texts themselves, not just what others say about them. There’s a reason the Bible sits on hotel nightstands, not annotated commentaries. The same principle applies to constitutional law. Before we dive into interpretive wars, doctrinal battles, and footnote-heavy judicial opinions, there’s value in that moment of direct encounter with the text.

When I ask students to simply read the Fourteenth Amendment without any scholarly commentary, something interesting happens: they start asking the questions that have been driving constitutional interpretation for centuries.

“What exactly does ‘due process’ mean?”

The Fifth Amendment says no person shall be “deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” The Fourteenth Amendment repeats this constraint, applying it to the states. But neither amendment defines “due process.” Is it just about procedure—did the government follow the right steps? Or does it encompass substance—are there some things the government simply cannot do, no matter how careful the procedures?

These aren’t just academic puzzles. The evolution from “procedural” to “substantive” due process gave us everything from Lochner’s economic liberty to Griswold’s privacy rights. All from two little words that sound so ... bureaucratic.

“What are these ‘privileges or immunities’ anyway?”

The Fourteenth Amendment declares that “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.” Sounds important, right? It sits right there between the Citizenship Clause and the Due Process Clause, in prime real estate.

Yet this clause has been gathering dust since the Slaughter-House Cases gutted it in 1873. Students read it and think, “This sounds important.” They’re not wrong—it was supposed to be the main event. It was the clause that could have applied the Bill of Rights to the states immediately, completely, and cleanly. Instead, we got selective incorporation through the Due Process Clause, one painstaking case at a time.

The Beautiful Ambiguity

Maybe the most striking thing about reading the Constitution cold is how much it doesn’t say. The Equal Protection Clause simply states that no state shall “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” Equal protection from what? Of what laws? What constitutes equal treatment?

The First Amendment’s Free Speech Clause is breathtakingly brief: “Congress shall make no law ... abridging the freedom of speech.” What’s speech? When can it be abridged? What about the states—oh wait, that comes later, through incorporation.

Modern Echoes in Ancient Text

When I have students read the Free Exercise Clause (“Congress shall make no law... prohibiting the free exercise [of religion]”), they don’t yet know they’re encountering the tension between religious liberty and anti-discrimination laws, between faith and public accommodations, between belief and action that defines so many contemporary debates.

I bring fifteen years of litigating and writing about religious liberty cases to this classroom, but here’s what I find fascinating: watching students grapple with these nine simple words before they know the case law, before they understand the doctrinal frameworks I spent a decade and a half working within. Their fresh eyes see tensions and possibilities that practitioners sometimes miss. What exactly is “free exercise”? When does it end? What makes something “religious”?

This textual moment matters precisely because it’s separated from my war stories. Students need to see these words as they are, not as I’ve experienced them in practice.

The Constitutional Crisis Hiding in Plain Sight

Perhaps most interesting is watching students grapple with the Constitution’s silence on its own enforcement. Article III creates federal courts and grants them judicial power, but nowhere does the text say courts can declare laws unconstitutional. We get judicial review from Marbury v. Madison, not from the Constitution itself.

And what happens when the President simply ignores a court order? The Constitution provides no clear answer. It tells us the President “shall take care that the laws be faithfully executed,” but what if the President decides the judicial interpretation of those laws is wrong? The text offers no mechanism for courts to enforce their own orders.

These silences aren’t bugs—they’re features. The Constitution’s ambiguity isn’t a flaw to be fixed but a space for democratic interpretation, constitutional development, and ongoing negotiation about what our fundamental commitments mean.

Like sacred texts that speak differently to each generation, the Constitution’s meaning evolves not because the words change, but because we change. And perhaps that’s exactly as the Framers intended.

The Pedagogical Moment

Starting with the text creates a crucial pedagogical moment. Before students learn that substantive due process is “controversial” or that incorporation is “settled,” they get to wonder why these simple words have caused so much trouble. Before they know the “right” answer about what equal protection means, they get to struggle with why equality might be hard to define.

This isn’t just constitutional law teacher nostalgia. That moment of textual innocence reveals something important: these aren’t technical legal problems with obvious answers. They’re questions about how we want to live together, what rights matter, and who gets to decide. The ambiguity isn’t a weakness—it’s where democracy happens.

When we move too quickly to doctrine and precedent, we can lose sight of the fact that all this elaborate jurisprudential machinery springs from strikingly simple language. “Equal protection.” “Due process.” “Free speech.” These are human words for human aspirations, not magical legal formulas.

Next Up

In my next post, I explore a forgotten chapter of American constitutional history—when the Bill of Rights didn’t apply to the states at all. It’s part legal reflection, part thought experiment: What would it mean to live in a country where your rights changed the moment you crossed a state line? What did federalism originally ask of us, and what kind of constitutional imagination did we lose when national rights began to override local governance?

This isn’t a dive into doctrine just yet—it’s a meditation on geography, sovereignty, and the strange idea that the First Amendment once didn’t protect you from your own state.

Until then, go read the Constitution. Really read it. Notice what it says—and what it doesn’t. And maybe ask yourself what kind of country we built before incorporation changed everything.

In the section titled "What are these ‘privileges or immunities’ anyway?”

You write "[i]t was the clause that could have applied the Bill of Rights to the states immediately, completely, and cleanly. Instead, we got selective incorporation through the Due Process Clause, one painstaking case at a time."

I would argue this was intentional and how the Founders envisioned constitutional change. Gradual and incremental progress acts as an inherent check on Judicial overreach and as an additional safeguard against tyranny. This view is further supported by James Madison's Federalist Papers. In Federalist 51, he argued that separating power and forcing a slow pace of significant change was essential to preventing any one branch from dominating.

I appreciate the history behind the dates and reviewing the amendments by what was going on in the country at a macro level. Our constitution was drafted and signed when there was so much the drafters could not have known - the internet (when drafting about copyright protections), mass migration and technology like airplanes (when drafting about citizenship rights, etc), assault rifles and weapons of mass destruction (when drafting the second amendment).

The comparison to religious text is spot on. I hear people say "the ____ is clear . . . " when discussing different religious texts or the constitution and I find it interesting because so much of the argument, disagreement, history, and court cases stems from the fact that they are emphatically not clear. Within years of drafting the constitution came the need for amendments -- recognizing that when "We, the people" and our societal "norms" change, our laws should too.