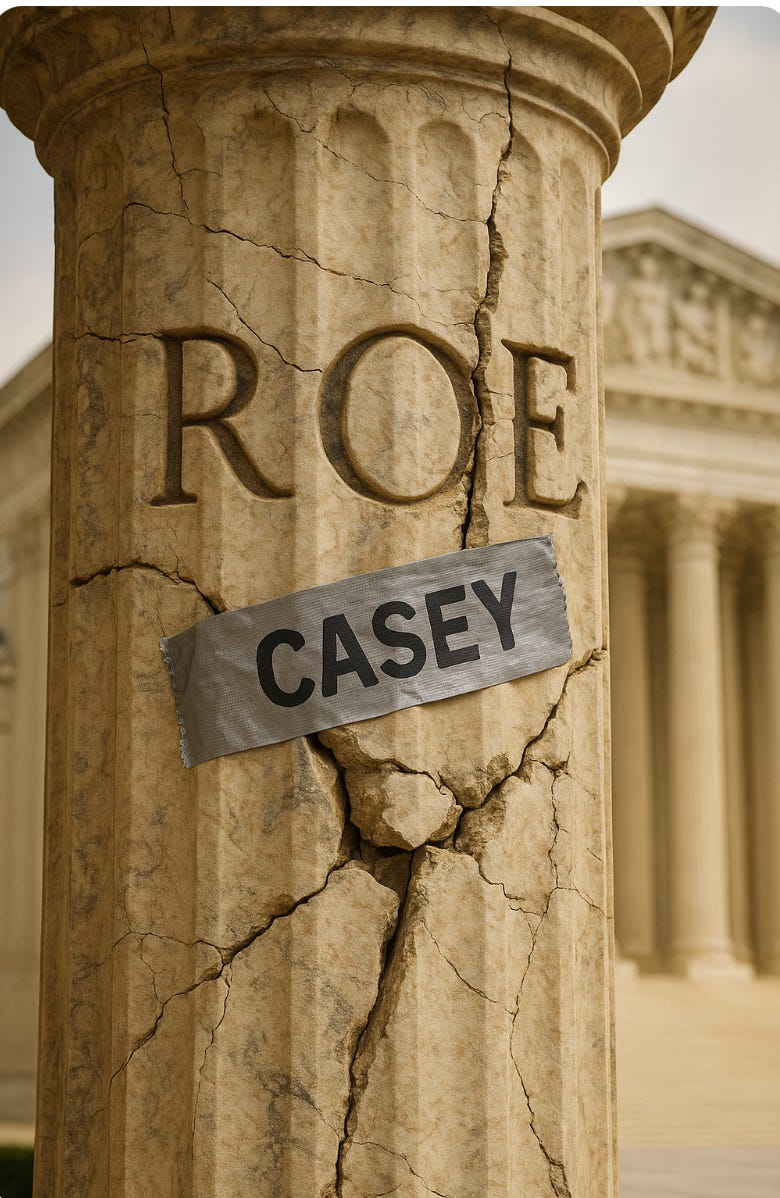

13. The Cracked Foundation

How Planned Parenthood v. Casey tried to save Roe by weakening it

Holding On and Letting Go

In Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), the Supreme Court stood at a constitutional crossroads. The political winds had shifted. The Court had changed. But in a surprise twist, the Justices didn’t overturn Roe v. Wade.

They reaffirmed it—kind of.

Casey held that the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause still protected a woman’s right to have an abortion before fetal viability.

But the Court abandoned Roe’s trimester framework, replacing it with something more elastic—and more opaque: the undue burden standard.

Under this new rule, a law would be unconstitutional if it placed a substantial obstacle in the path of a person seeking an abortion before viability.

Sounds clear enough. It wasn’t.

What Casey Actually Did

The Court sorted through a set of Pennsylvania abortion restrictions. Here’s how they ruled:

24-hour waiting period → ✅ Upheld

Informed consent requirement → ✅ Upheld

Parental consent for minors (with judicial bypass) → ✅ Upheld

Spousal notification → ❌ Struck down

Recordkeeping and reporting requirements → ✅ Upheld

Why was spousal notification different? Because for women in abusive relationships, requiring them to inform their husbands could be coercive, dangerous—even life-threatening. That, the Court said, was a substantial obstacle.

But a 24-hour delay or forced disclosure to parents? Not enough to trigger constitutional concern.

Liberty, Mystery, and Meaning

The heart of Casey wasn’t doctrinal—it was philosophical.

In one of the most-quoted passages in modern constitutional law, the Court declared:

“At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.”

It was a soaring affirmation of autonomy. But critics pounced: was this liberty too abstract, too metaphysical to guide real-world policy?

And yet, it hinted at something powerful—that reproductive choice was not just about medical procedures or trimesters. It was about identity, freedom, and self-governance.

“Undue Burden” in Action

In the years that followed, courts tested the new standard:

🧑⚖️ Parental Consent → Upheld with judicial bypass (Bellotti v. Baird)

🕒 Waiting Periods → Usually upheld (Casey)

📋 Recordkeeping → Often upheld if tied to legitimate interests

💍 Spousal Consent → Consistently struck down (Danforth, Casey)

🏥 Second-trimester hospital requirements → Sometimes struck down (Akron)

One thread uniting these cases: context matters. An obstacle isn’t automatically a burden—but it might be, depending on how it plays out in real life.

But What About Funding?

Here’s where things get even murkier.

The Court made clear that while Roe and Casey protected a right to choose abortion, they did not require the government to help fund it.

Maher v. Roe (1977): States don’t have to cover elective abortions through Medicaid.

Harris v. McRae (1980): The Hyde Amendment, which barred federal funding for most abortions, was upheld—even for those who couldn’t afford the procedure.

Rust v. Sullivan (1991): Clinics receiving federal funds could be banned from even counseling patients about abortion.

The message was clear: Roe gave you a right—but it didn’t come with a check.

Justice Thurgood Marshall warned that Harris made abortion “a luxury for the rich.” And Justice Blackmun, the author of Roe, accused the majority in Rust of condoning viewpoint discrimination—gagging federally funded doctors from even mentioning a constitutionally protected option.

Is a Right Without Access Still a Right?

The dissenters didn’t think so.

They argued that when abortion is legal but economically unreachable, the right becomes hollow—especially for low-income women, women of color, and those in rural areas.

The majority insisted that the Constitution protects against government interference, not economic inequality. But that distinction struck many as detached from reality.

What does reproductive liberty mean in a world without Roe or Casey? And what happens when constitutional rights are easier to pronounce than to practice?

I quite enjoyed class today, and I believe the classification of abortion as a negative right was the constitutionally correct interpretation under Harris and Maher. However, I did not find the majority opinion of Casey or dissent in Dobbs to be particularly compelling. Both opinions stress the importance of stare decisis. I think this assertion is especially weak because both Justices Breyer and Sotomayor voted to ignore stare decisis and overturn a 50 year precedent of Apodaca v. Oregon in Ramos v. Louisiana, 590 U.S. 83. - Which was decided just two years before Dobbs.

Justice Gorsuch wrote in Ramos, "But stare decisis has never been treated as “an inexorable command.” And the doctrine is “at its weakest when we interpret the Constitution” because a mistaken judicial interpretation of that supreme law is often “practically impossible” to correct through other means. To balance these considerations, when it revisits a precedent this Court has traditionally considered “the quality of the decision’s reasoning; its consistency with related decisions; legal developments since the decision; and reliance on the decision.” 590 U.S. 83, 105-106. Casey and the Dobbs dissent rely heavily on reliance. I disagree that reliance interests should matter at all in questions of constitutional interpretation. That is a policy arguement for legislatures and voters, not for unelected judges.

I believe the only thing that should matter when revisting prior precedent is whether the interpretation was incompatible with the Constitution. I think the majority in Dobbs fleshed this out well.

That said, I found myself agreeing with large parts of the Dobbs dissent. Although, I found the language regarding other substantial due process decisions being on the chopping block to be inappropriate and unwarranted. However, the portions I did agree with were not constitutional arguments regarding why Roe and Casey were correct. The dissent instead focused on the importance of abortion access and utilized figures to show a substantial amount of women access this care in their lifetimes. This is, however, something that must be left to the legislature, and if needed, the constitutional amendment process.

To conclude, legitimacy, public reaction, reliance, and policy arguements should not be the canons upon which whether precedent should be upheld. But rather, was the prior decision incompatible with the constitution? I believe Dobbs got that correct.

I wonder how my reasoning, or the cases since Roe, may differ if Roe was decided according to Equal Protection rather than Due Process.

The philosophical underpinning of Casey is beautiful but horribly misplaced. Oft-quoted, it has served as a punchline just as much as an aspiration, depending on which judge wields it. The majority ought to have seen the weakness they were threading into precedent by basing the decision on this amorphous design that strangely mirrors a natural law mindset. The 'undue burden' standard further confused the available restrictions and caused accessibility issues to proliferate. In the end, it was inevitable that Casey would eventually lead to such a reduction in availability for abortion that the procedure would have, in effect, been banned for much of the country, even if Dobbs had never come to pass.