15. The Day Constitutional Law Changed

Understanding Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization

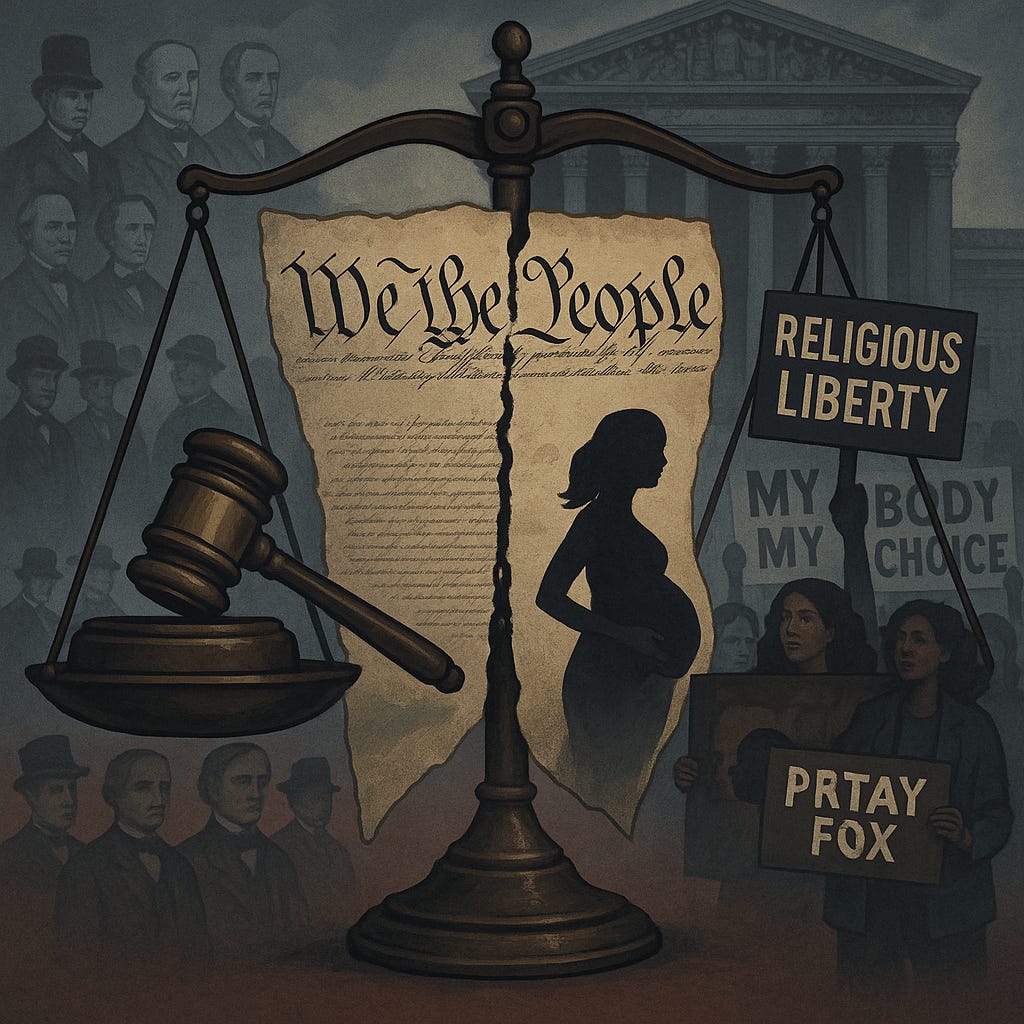

On June 24, 2022, the Supreme Court handed down Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, fundamentally reshaping American constitutional law. But what exactly did the Court decide? And why did the justices disagree so sharply about how to get there?

The Basic Facts: Mississippi's 15-Week Ban

The case began simply enough. In 2018, Mississippi passed the Gestational Age Act, banning most abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy. Jackson Women's Health Organization—Mississippi’s only remaining abortion clinic—sued, arguing the law violated Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which protected abortion rights until fetal viability (around 24 weeks).

Lower courts struck down Mississippi’s law as clearly unconstitutional under existing precedent. But Mississippi appealed to the Supreme Court with an audacious request: don’t just uphold our 15-week ban—overturn Roe and Casey entirely.

The Court said yes.

The Majority Opinion: Justice Alito's Constitutional Revolution

Justice Alito, writing for five justices (Thomas, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett), didn’t just uphold Mississippi's law—he eliminated the constitutional right to abortion altogether.

The Core Holding: The Constitution does not protect a right to abortion. States can now regulate or ban abortion as they see fit.

The Historical Argument: Alito’s opinion relied heavily on laws from 1868, when the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified. His reasoning was straightforward: if three-quarters of states had criminalized abortion by 1868, then the Fourteenth Amendment couldn’t have been intended to protect abortion rights. The Court looks for rights that are “deeply rooted in the Nation's history and tradition”—and abortion, Alito argued, fails that test.

Rejecting Precedent: The majority threw out the usual rule that courts should respect prior decisions (stare decisis). Why? Because Roe and Casey were “egregiously wrong” from the start. Alito compared overturning Roe to Brown v. Board of Education overturning Plessy v. Ferguson—sometimes the Court must correct its mistakes.

The Key Distinction: What makes abortion different from other privacy rights? According to Alito, abortion “destroys what those decisions called ‘potential life,’”setting it apart from contraception or same-sex marriage cases.

Three Different Concurrences, Three Different Visions

Justice Thomas: Burn It All Down

Thomas agreed with the result but wanted to go much further. His concurrence was a constitutional bomb: he called for reconsidering “all of this Court's substantive due process precedents,” explicitly naming:

Griswold (contraception rights)

Lawrence (same-sex intimacy)

Obergefell (same-sex marriage)

Thomas argued that “substantive due process” is an “oxymoron”; due process is about procedures, not protecting unenumerated rights. His message was clear: if you thought Dobbs was just about abortion, think again.

Justice Kavanaugh: Nothing to See Here

Kavanaugh took the opposite approach, emphasizing the Court’s supposed neutrality. His concurrence stressed that Dobbs only affects abortion and that other precedents remain safe. Key points:

The Constitution is “neutral” on abortion, so the Court must be, too

Overturning Roe “does not threaten or cast doubt” on contraception or same-sex marriage cases

States cannot prevent women from traveling to other states for abortions

Kavanaugh’s concurrence read like damage control—reassuring readers that the constitutional revolution stops here.

Chief Justice Roberts: The Middle Ground That Wasn’t

Roberts agreed with the outcome but criticized the majority for going too far. His approach:

Uphold Mississippi’s 15-week ban

Abandon the “viability” line from Roe and Casey

But don’t eliminate abortion rights entirely

Roberts saw the majority’s decision as an “unnecessary and disruptive ruling” that created needless “political turmoil.” He wanted surgical precision; the majority chose a sledgehammer.

The Dissent: Constitutional Apocalypse

Justices Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan wrote a joint dissent that was part legal argument, part dire warning. Their main points:

On History: The majority’s approach “freezes constitutional rights in the past.” The Constitution was designed for “ever-changing circumstances over centuries.” Plus, the 1868 laws the majority relied on were written by men—women weren’t even considered full members of the constitutional community.

On Precedent: Overturning Roe and Casey violates everything courts stand for. The majority “substitutes a rule by judges for the rule of law.”

On Consequences: “After today, young women will come of age with fewer rights than their mothers and grandmothers had.” The decision will create “interjurisdictional abortion wars” and invite a host of new constitutional conflicts.

The Bottom Line: “No one should be confident that this majority is done with its work.”

What Makes This Decision So Unusual

Most Supreme Court decisions either expand rights or narrow them incrementally. Dobbs is different—it eliminated a constitutional right that had existed for nearly 50 years. That’s extraordinarily rare in American constitutional law.

The justices’ sharp disagreement over methodology is equally significant:

The majority: History from 1868 determines constitutional rights

Thomas: Substantive due process should be eliminated entirely

Kavanaugh: This decision changes nothing else

Roberts: Courts should move incrementally, not dramatically

The dissenters: Constitutional rights must evolve with society

The Immediate Aftermath

Within hours of the decision, states began implementing abortion bans. Some had “trigger laws” that automatically banned abortion when Roe fell. Others had pre-Roe bans that suddenly became enforceable again.

The result: a patchwork of laws where abortion access depends entirely on geography. Drive across a state line, and your constitutional rights might disappear.

Why This Matters Beyond Abortion

Dobbs isn’t just about reproductive rights—it’s about how the Supreme Court interprets the Constitution. The decision suggests a Court increasingly willing to:

Overturn longstanding precedent

Rely heavily on historical practices from the 1800s

Narrow the scope of unenumerated rights

Whether you support or oppose the outcome, Dobbs represents a fundamental shift in constitutional methodology that will influence American law for decades.

Next time, I’ll dive deeper into one of the most contentious aspects of the Dobbs decision: the concept of “reliance” and why the Court concluded that women’s dependence on abortion access was too “generalized” to matter constitutionally.

What did you think of the Court’s reasoning? Was the majority right to prioritize historical practices from 1868, or should constitutional rights evolve with society?

I find the “deeply rooted in the Nation's history and tradition” test extremely flawed, and specifically the manner in which it was used in Dobbs. The Court looked back at antiquated common law and the criminalization of abortion in 1868. As we know, women were not able to "engage" in the democratic process until 1920 when the 19th Amendment was passed. How can the Court rely on a test where the rights of that group were not even represented at that time? It is incredibly ironic considering the Court decides to leave it to the states and the "democratic process."

Reading Planned Parenthood v. Casey, I believe the Court was attempting to create a shield by not going into detail on women's autonomy and individual liberty. Rather, they focused on stare decisis, which I think was a statement: "if you overturn Casey, the Court will lose its legitimacy." By refraining from going into more details on a woman's right to "choose," the Court seemed to be rather intentional in remaining neutral to protect its holding and the potential argument that they were acting as "biased Justices." However, this strategy failed, and I agree with the dissent of Dobbs--it was solely because of the makeup of the Court.

I believe the dissent in this case made a strong argument when it pointed out that the majority's reasoning relied on the fact that the right to an abortion was not "deeply rooted in the nation's history," but neither were most of the other rights the majority claims it is not tampering with. I believe that this argument from the dissent significantly undermines the majority's reasoning by highlighting the selective nature of its historical perspective. Abortion was not widely accepted when the 14th Amendment was ratified, but neither was same-sex marriage, and as Justice Kavanaugh's concurrence highlights, this ruling should not affect the rights guaranteed in cases like Griswold, Eisenstadt, Loving, and Obergefell. Regardless of whether you believe Constitutional rights should evolve with society, there at least needs to be some level of consistency in the argument.