19. The Door Slammed Shut

Bowers v. Hardwick and the constitutional closet

It starts with a knock—or maybe more accurately, a betrayal of the threshold. In 1982, Michael Hardwick’s life became the site of a constitutional reckoning when police officers, armed with a warrant for a minor infraction, entered his home and found him in bed with another man. Both were arrested under Georgia’s sodomy law, a statute that criminalized “any sexual act involving the sex organs of one person and the mouth or anus of another.”

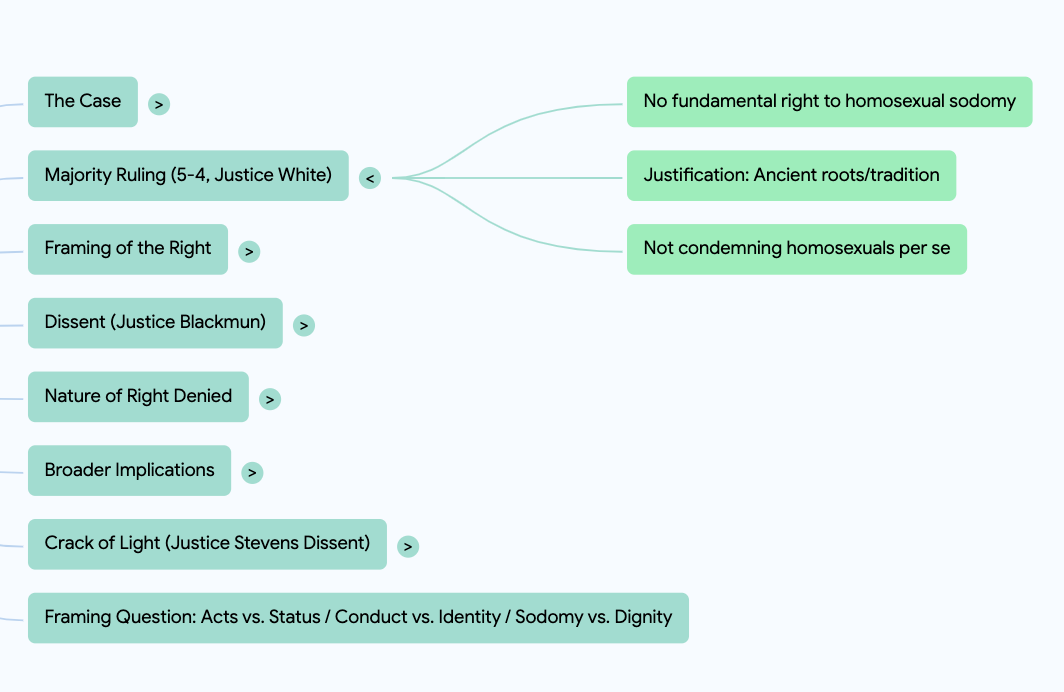

By the time the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 1986, the question had narrowed to a blunt point: Does the Constitution confer “a fundamental right upon homosexuals to engage in sodomy”?

Justice White’s answer for the 5-4 majority was crisp:

“We hold that the Constitution does not confer a fundamental right to engage in homosexual sodomy.”

He justified the decision by invoking tradition: “Proscriptions against that conduct have ancient roots,” and he insisted the Court was not condemning homosexuals per se, just declining to create a right that lacked deep historical precedent.

Framing the issue as a claim to a fundamental right to sodomy was everything. In constitutional law, the level of generality at which you define a right often determines whether it lives or dies. If you ask whether there’s a right to same-sex intimacy, the Court must reckon with personal autonomy. If you ask whether there’s a right to “homosexual sodomy,” the path to denial is paved with historical disapproval.

Justice Blackmun’s dissent zeroed in on this point:

“This case is no more about ‘a fundamental right to engage in homosexual sodomy’ than Stanley v. Georgia was about a fundamental right to watch obscene movies, or Katz v. United States was about a fundamental right to place interstate bets from a telephone booth.”

The real issue, he argued, was the right to be let alone, what Justice Brandeis once called “the most comprehensive of rights and the right most valued by civilized men.”

What’s especially striking is that this wasn’t a request for a positive right. Hardwick wasn’t asking the state to recognize a relationship, provide a license, or confer benefits. He was asking for a shield, not a sword—for the state to stay out of his bedroom. This was as classically negative a right as you can get: freedom from government intrusion into private life. That the Court said no even to this is what made Bowers such a profound loss.

The opinion is often remembered for what it denied, but it’s equally important to notice how it denied. The majority insisted that “any claim that these cases [on privacy] nevertheless stand for the proposition that any kind of private sexual conduct between consenting adults is constitutionally insulated from state proscription is unsupportable.” The Court didn’t merely refuse to expand privacy rights; it actively eroded them.

Beyond the doctrinal defeat, Bowers delivered a profound cultural verdict: gay relationships existed outside the realm of constitutional dignity. Intimate bonds between same-sex partners were reduced to something illicit, contraband-like in the eyes of the law. The closet, it turned out, wasn’t just a social construct; it had judicial enforcement.

And yet, even in shutting the door, the Court left a crack of light. As Justice Stevens noted in his dissent, the Georgia law criminalized acts regardless of the participants’ sexual orientation—but in practice, it was only enforced against gay men. The statute is, in practice, a means of expressing disapproval of homosexuality, he wrote. And that selective enforcement raised equal protection concerns the majority ignored.

Bowers didn’t fully embrace the principle that laws based solely on moral disapproval might fail constitutional review. But this principle would become central to a very different ruling a decade later.

So the framing question lingers: Is this about acts or about status? Conduct or identity? Sodomy or dignity?

Because how you frame the question often shapes the answer. And in Bowers, the question was framed to be answered with rejection.

Next: What happens when the law doesn’t criminalize your existence, but denies you any shield from discrimination?