20. The Law of Exclusion

Romer v. Evans and the turn toward equality

Ten years after Bowers v. Hardwick, the legal terrain for LGBTQ+ rights looked mostly unchanged. Sodomy laws still stood. The Court had not revisited its decision. LGBTQ+ Americans continued to live under the shadow of criminalization. But beneath the surface, something had changed. The public now understood the issue differently, and judges began to describe harm in new ways.

The case didn’t come from a criminal statute this time. It came from a referendum.

In 1992, Colorado voters passed Amendment 2 to the state constitution, prohibiting any state or local government entity from recognizing homosexual, lesbian, or bisexual orientation as a protected class. More precisely, it said no branch of government could enact or enforce laws that gave LGBTQ+ people grounds to claim discrimination in housing, employment, education, or public accommodations.

The amendment didn’t criminalize gay people. It just made them legally invisible.

This distinction matters. By the time Romer v. Evans reached the Supreme Court in 1996, the legal question wasn’t about privacy or intimacy, it was about access to the law itself. Could a state carve out an exception to equal protection and declare that one group of citizens was barred from even seeking the protections others enjoyed?

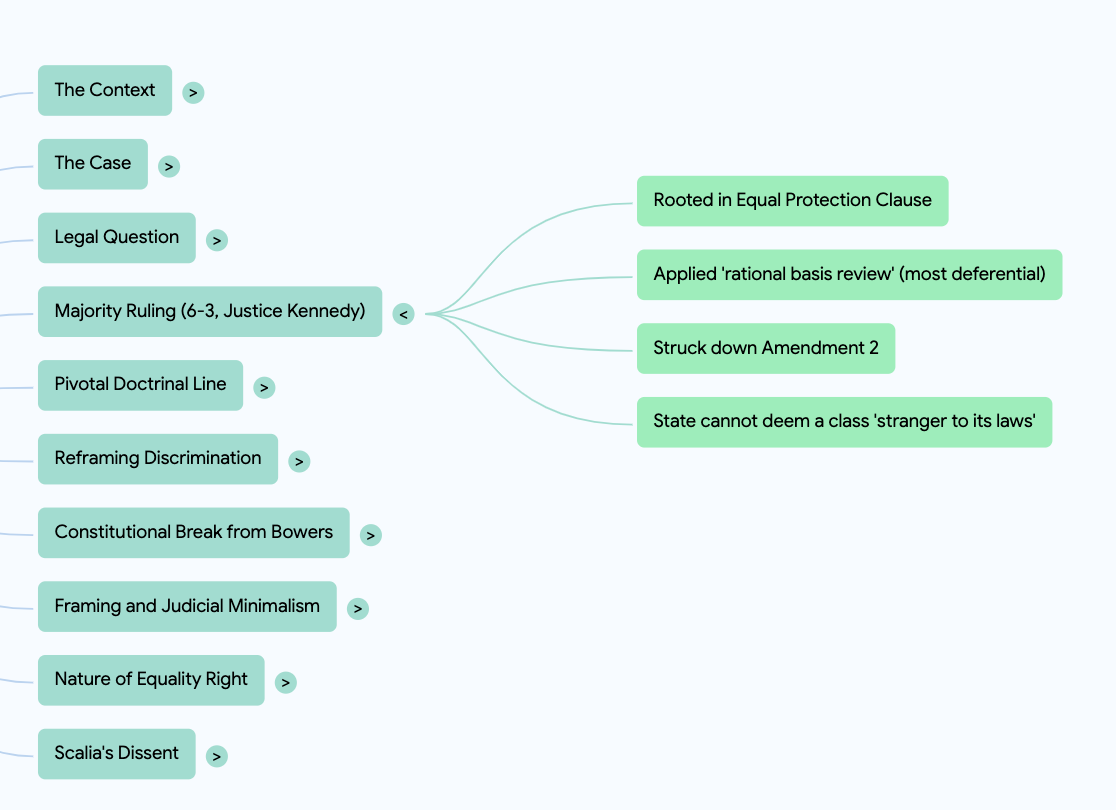

Justice Kennedy, writing for a 6–3 majority, said no.

“A State cannot so deem a class of persons a stranger to its laws,” he wrote. Amendment 2 “imposes a special disability upon those persons alone.”

The ruling was rooted in the Equal Protection Clause. Technically, the Court applied rational basis review, the most deferential standard of constitutional scrutiny. But it didn’t look like any rational basis test we’d seen before. The Court wasn’t interested in hypothetical justifications. It asked a deeper question: What was this law really doing?

“If the constitutional conception of ‘equal protection of the laws’ means anything,” Kennedy wrote, “it must at the very least mean that a bare... desire to harm a politically unpopular group cannot constitute a legitimate governmental interest.” (Romer, quoting Dept. of Agriculture v. Moreno, 1973).

That line about a “bare desire to harm” became doctrinally pivotal. Kennedy didn’t accuse the state of outright hatred. He didn’t need to. Amendment 2 was constitutionally defective not because it punished a group directly, but because it structurally denied them legal recourse. The law created a kind of constitutional quarantine: other groups could seek protection under the law, but this group defined solely by sexual orientation could not.

In effect, Romer reframed what discrimination looks like. Harm doesn’t require handcuffs or jail time. It can be inflicted in the denial of political belonging. As Kennedy put it, “the amendment has the peculiar property of imposing a broad and undifferentiated disability on a single named group.” It didn’t just violate equal protection; it denied participation in the legal system itself.

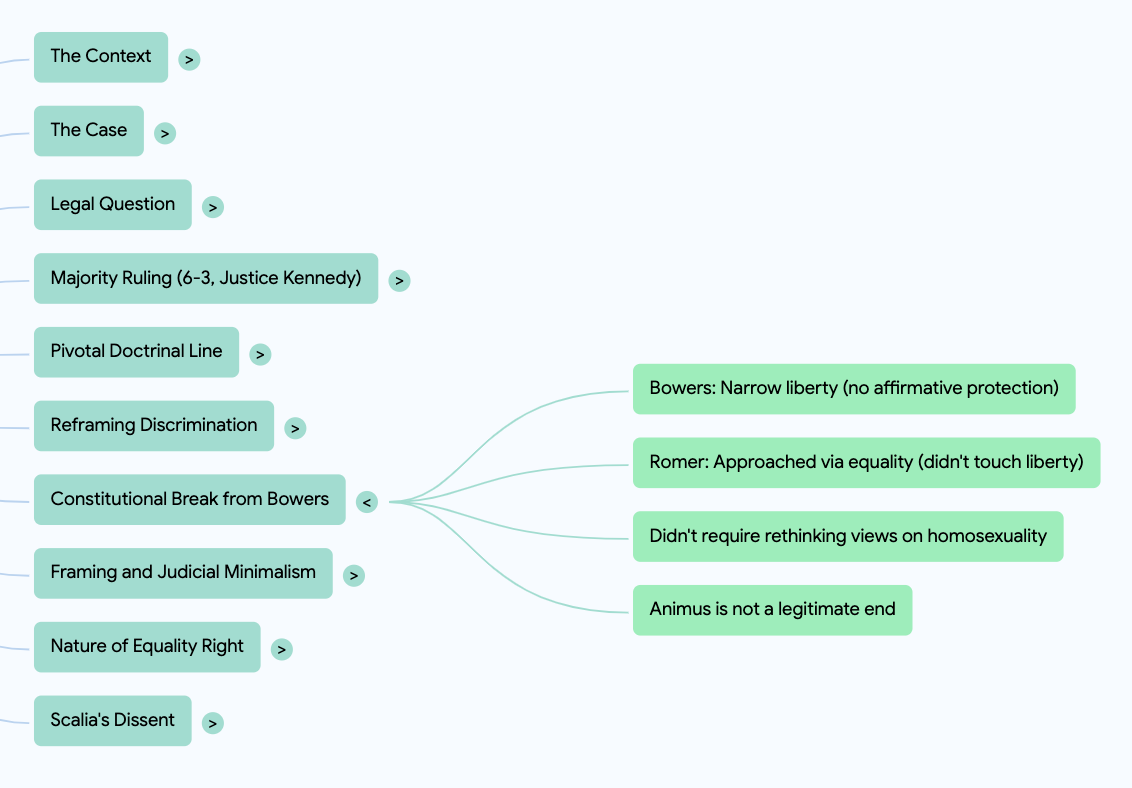

That’s what made Romer a constitutional break from Bowers—even though the Court didn’t say so explicitly. Bowers had taken a narrow view of liberty: no affirmative constitutional protection for private same-sex intimacy. Romer didn’t touch liberty at all. It approached the issue through equality, and that made all the difference.

It also made the ruling harder to dismiss. The majority wasn’t asking the country to rethink its views on homosexuality. It was simply demanding that laws serve legitimate ends. And “animus,” Kennedy concluded, is not a legitimate end.

Framing and Judicial Minimalism

It’s easy to read Romer as a cautious opinion. It doesn’t name Bowers. It doesn’t speak of dignity or intimacy. It avoids broad declarations of LGBTQ+ rights. But that’s part of its brilliance. The Court chose a path that was constitutionally straightforward and rhetorically accessible: treating Amendment 2 as an outlier, a legal aberration that couldn’t be justified under even the most lenient standard.

But minimalism can be powerful when it subtly shifts the doctrinal landscape.

Scholars sometimes refer to Romer as the origin point of “rational basis with bite.” It used the lowest tier of scrutiny to strike down a law that most lower courts might have upheld. Why? Because the harm was so sweeping, the exclusion so explicit, that even minimal scrutiny was too much for the law to survive.

That decision created doctrinal breathing room. The Court could now strike down discriminatory laws without recognizing new fundamental rights. It could work within the familiar terrain of equal protection—but with an alertness to the real-world consequences of exclusion.

What Kind of Right Is Equality?

Are we dealing with a negative right (freedom from state interference) or a positive one (a claim to state recognition or protection)? Romer blurs the line.

On one level, Amendment 2 denied a positive right—the ability to seek redress under anti-discrimination laws. But on a deeper level, it imposed a negative burden. It took away access that others had. It wasn’t just failing to affirm a status, it was using law to deny the tools of legal belonging.

So even though Romer is technically an equal protection case, it sounds a lot like a structural due process one. It doesn’t rely on privacy or intimacy. But it does recognize that government cannot wall off a disfavored group from the architecture of civil life.

Scalia’s Warning, Kennedy’s Silence

Justice Scalia’s dissent reads like a thunderclap. He accused the Court of favoring “the politically powerful homosexual lobby” and warned that Romer would pave the way to same-sex marriage. “This Court,” he wrote, “has no business imposing upon all Americans the resolution favored by the elite class from which the Members of this institution are selected.”

Scalia wasn’t wrong about the trajectory. Romer didn’t mention marriage, but it introduced a moral shift. If a law grounded in disapproval isn’t enough to justify exclusion, then the burden would soon fall on every law that treated LGBTQ+ identity as suspect.

Scalia saw where the logic led. Kennedy was already walking there.

Doctrinal sum-up:

The Equal Protection Clause bars laws rooted in a “bare desire to harm” politically unpopular groups.

The Court used rational basis review but in a more searching way—often called “rational basis with bite”—to strike down the law.

This marked a shift from earlier privacy-focused LGBTQ+ cases to one centered on structural equality, signaling that exclusion itself can be unconstitutional even without recognizing a new fundamental right or suspect class.

Next: When the Court returns to the question of liberty, overturns Bowers, and recognizes dignity as a constitutional value.