21. The Right to Be

Lawrence v. Texas and the undoing of shame

It starts with another arrest.

In 1998, police entered John Lawrence’s apartment in Houston after a false report about weapons. Inside, they found Lawrence and Tyron Garner, two men, engaged in consensual sex. They were arrested under Texas’s “Homosexual Conduct” law, which made it a crime for two people of the same sex to have certain types of intimate contact.

The law didn’t apply to heterosexual couples. It singled out gay people. It didn’t punish violence or public behavior—it punished private intimacy.

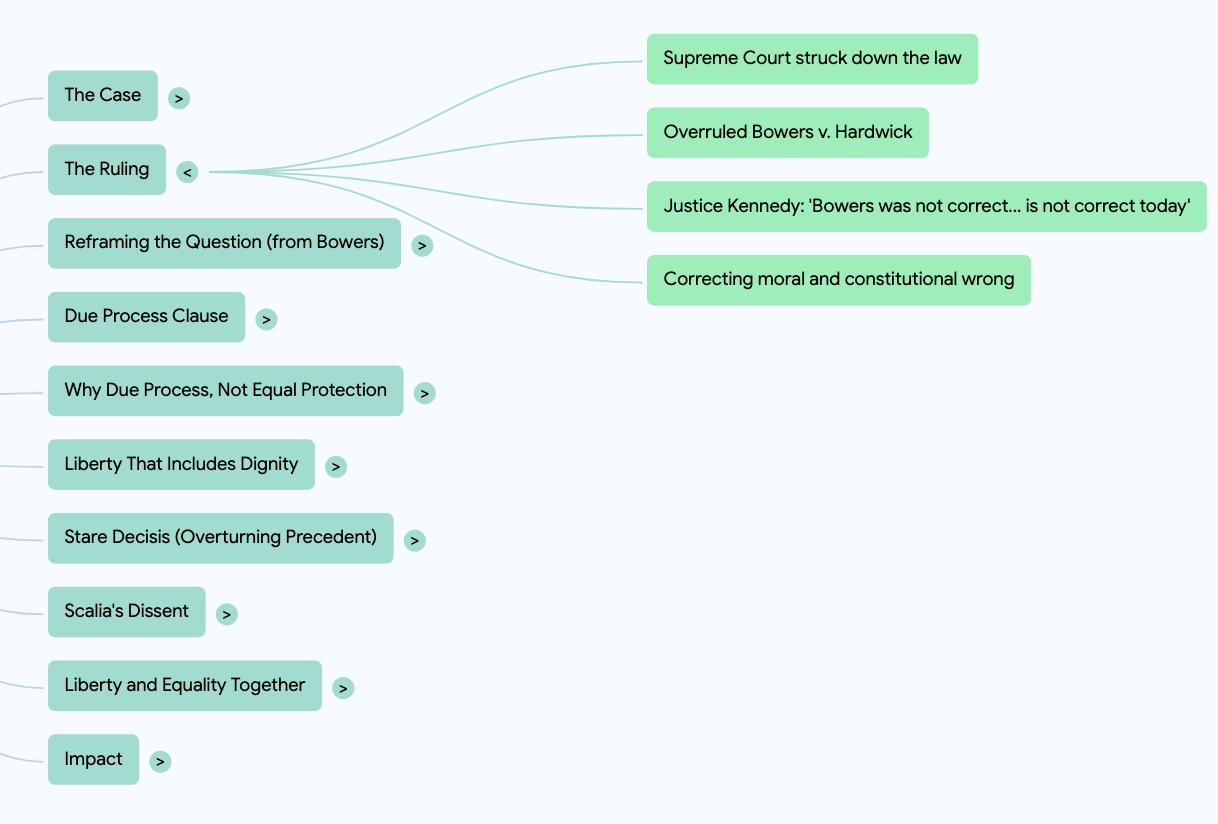

The case made its way to the Supreme Court. And this time, the Court did what it hadn’t done before. It struck down the law—and it overruled Bowers v. Hardwick.

Justice Kennedy wrote the opinion for the Court:

“Bowers was not correct when it was decided, and it is not correct today. It ought not to remain binding precedent. Bowers v. Hardwick should be and now is overruled.”

This wasn’t just about changing the law. It was about correcting a moral and constitutional wrong.

From Criminalization to Constitutional Protection

In Bowers, the Court had framed the question narrowly: is there a fundamental right to engage in homosexual sodomy?

That framing led the Court to say no.

But Lawrence reframed it: does the Constitution protect the liberty of adults to make private decisions about their intimate lives?

This time, the answer was yes.

Justice Kennedy wrote:

“Their right to liberty under the Due Process Clause gives them the full right to engage in their conduct without intervention of the government... The State cannot demean their existence or control their destiny by making their private sexual conduct a crime.”

The decision wasn’t about approving or disapproving of anyone’s behavior. It was about recognizing that the government has no business criminalizing consensual adult relationships in private.

Why the Court Used Due Process, Not Equal Protection

Some expected the Court to strike down the law using the Equal Protection Clause. After all, the Texas law only applied to same-sex couples—it treated people differently based on sexual orientation.

Justice O’Connor took that approach in her concurring opinion. She said:

“A law branding one class of persons as criminal solely based on the State’s moral disapproval of that class and the conduct associated with that class runs contrary to the values of the Constitution.”

But the majority didn’t go that route. Why?

Because if Texas had rewritten the law to criminalize everyone (same-sex and different-sex couples) the unequal treatment would go away, but the intrusion into private life would remain.

So the Court used substantive due process. It said the real problem was not that the law treated people differently, but that it criminalized something the Constitution protects: the private liberty to make personal decisions about intimacy.

A Liberty That Includes Dignity

One of the big themes in Lawrence is dignity.

The Court didn’t just say the law was unfair—it said it was demeaning. It treated gay people as criminals for doing something that heterosexual people could do without penalty.

Kennedy wrote:

“When homosexual conduct is made criminal by the law of the State, that declaration in and of itself is an invitation to subject homosexual persons to discrimination both in the public and in the private spheres.”

In other words, laws like this don’t just punish behavior. They send a message: that certain people are less worthy of respect and protection.

This is why Lawrence was such a powerful rejection of Bowers. It wasn’t just a legal course correction. It was a moral one.

What About Stare Decisis?

The Court openly discussed why it was overturning Bowers. It said precedent is important, but not unchangeable.

“The doctrine of stare decisis ... is not an inexorable command.”

The Court gave three reasons:

Bowers was wrong when it was decided.

It hadn’t been relied on in ways that would make overturning it unfair.

It had been undermined by later cases, like Romer v. Evans.

The takeaway: sometimes the Court must correct itself, especially when a past decision has harmed real people and failed to live up to constitutional principles.

Scalia’s Dissent and What Comes Next

Justice Scalia dissented strongly. He warned that this decision would lead to recognition of same-sex marriage. He wrote:

“This effectively decrees the end of all morals legislation ... what justification could there possibly be for denying the benefits of marriage to homosexual couples exercising ‘the liberty protected by the Constitution’?”

Scalia saw what was coming. And in a way, he was right.

But the Court wasn’t ready to talk about marriage yet. Lawrence was about something more basic: that the government can’t make it a crime to be who you are, or to love who you love.

Liberty and Equality, Together

Even though the Court relied on due process, the themes of equality were everywhere. Lawrence is a good example of how the Constitution’s liberty and equality guarantees often overlap.

Sometimes courts treat liberty and equality as separate boxes. But in real life—and in this case—they work together. A law that criminalizes private relationships isn’t just an invasion of privacy. It’s also a statement about who deserves legal respect.

Lawrence did more than strike down a bad law. It changed how the Court talks about gay rights. It rejected criminalization. It affirmed dignity. And it made clear that constitutional liberty includes the right to personal, private relationships—without fear, shame, or arrest.

This wasn’t the end of the story. But it was the beginning of a new one.

Though I have been aware of this case for some time, actually sitting down and reading it was a shocking experience. To think basic, obvious liberties are held on by such a slim thread and were almost not established due to the rationale expunged in Scalia's dissent is terrifying. The shift from Bowers to Lawrence is stark. I wonder what Scalia would say now considering his more crude forewarnings have not come true.