14. The Shape-Shifting Shield

How “dignity” became constitutional law’s Swiss Army knife

Imagine you’re a Supreme Court Justice facing two different cases. In the first, you invoke “dignity” to strike down a law restricting personal autonomy. In the second, you invoke “dignity” to uphold a law that restricts that same autonomy. Sound contradictory? Welcome to the wonderfully complex world of constitutional dignity.

From Casey’s Dignity Framework to Constitutional Chaos

As I discussed in my last post, Casey established dignity as central to constitutional liberty, with that famous line about “the right to define one’s own concept of existence.” Casey’s dignity-based reasoning didn’t stay confined to abortion—it became the foundation for expanding gay rights through Lawrence, Windsor, and Obergefell (cases I’ll dive into in later posts).

But here’s where dignity doctrine gets messy: it started morphing in ways that seemed to contradict its original meaning.

The Carhart Puzzle: Where Dignity Gets Twisted

The real test of dignity doctrine came in the partial-birth abortion cases. Here’s where things get weird: these cases weren’t explicitly about dignity, but they revealed how the concept could be weaponized.

Stenberg v. Carhart (2000): Nebraska banned specific abortion procedures. The Court struck down the law under Casey’s undue burden test—no explicit dignity analysis, just straightforward application of precedent.

Gonzales v. Carhart (2007): Congress passed a nearly identical federal ban. This time, the Court upheld it. What changed wasn’t just the composition of the Court—it was the reasoning.

Justice Kennedy, writing for the majority in Gonzales, didn’t explicitly invoke dignity doctrine, but he smuggled in dignity-adjacent reasoning that turned Casey on its head. The government, he argued, had legitimate interests in promoting “respect for fetal life and ethical considerations.” More troubling, Kennedy suggested that protecting women from potentially regrettable decisions was itself constitutional—a paternalistic twist that seemed to contradict everything Casey’s dignity framework stood for.

Here’s the constitutional sleight of hand: Kennedy took Casey’s idea that dignity protects individual autonomy and flipped it—now dignity could justify restricting individual autonomy to protect people from their own choices.

The Dobbs Earthquake: Dignity’s Ultimate Test

The tension in dignity doctrine finally exploded in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022). The Court didn’t just overturn Roe—it explicitly rejected Casey’s dignity-based reasoning about abortion.

But here’s the constitutional puzzle: Dobbs left gay rights cases like Lawrence, Windsor, and Obergefell untouched. How can dignity simultaneously support same-sex marriage rights while being insufficient to protect abortion rights?

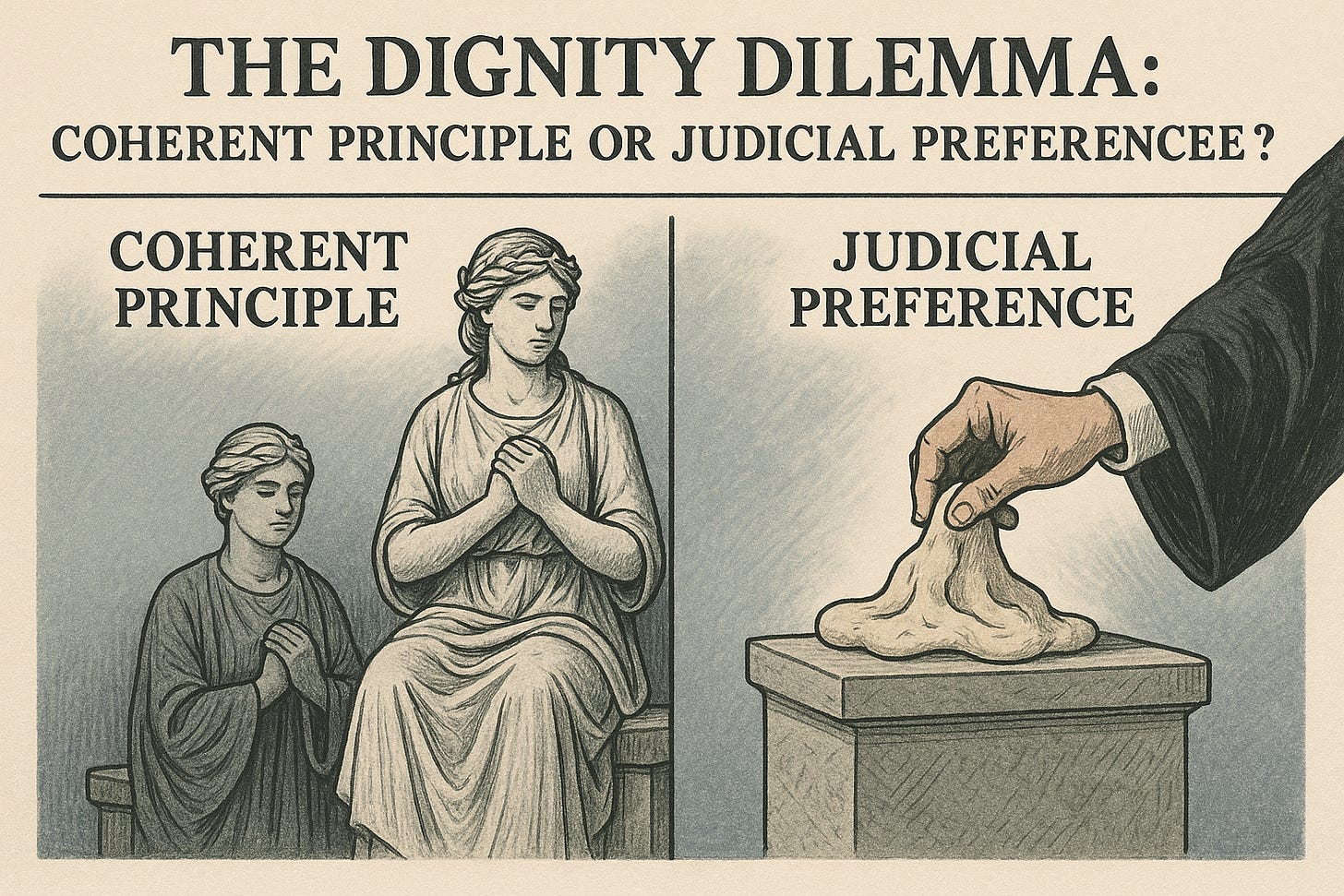

The Dignity Dilemma: Coherent Principle or Judicial Preference?

This brings us to the central question: Is dignity a meaningful constitutional concept, or just a fancy way for judges to dress up their policy preferences?

The case for coherence: All these cases do share a common thread—they’re about the government’s power to regulate intimate, identity-defining choices. Whether it’s reproductive decisions, sexual relationships, or marriage, dignity doctrine consistently asks: Should the state be able to interfere with deeply personal aspects of human existence?

The case for malleability: Critics argue that dignity is constitutional Play-Doh—it can be shaped to support whatever outcome a majority prefers. In Lawrence, dignity meant sexual autonomy. In Gonzales, dignity meant protecting women from their own decisions. In Dobbs, dignity apparently meant letting states ban abortion entirely.

What This Means for Constitutional Law (And Your Future Practice)

For law students and practitioners, dignity doctrine presents both opportunity and challenge:

Opportunity: Dignity provides a powerful rhetorical and legal framework for challenging government overreach in areas of personal autonomy. It’s particularly potent in cases involving LGBTQ+ rights, reproductive freedom, and end-of-life decisions.

Challenge: Dignity’s flexibility makes it unpredictable. A doctrine that can be used to both expand and contract rights isn’t much of a doctrine at all.

Practical tip: When arguing dignity-based claims, ground them in concrete harms and specific constitutional text. The more abstract your dignity argument, the easier it is for opposing counsel (or skeptical judges) to reshape it.

The Road Ahead

Dignity isn’t going anywhere in constitutional law—it’s too embedded in modern doctrine. But its future shape remains uncertain. Will the Court develop more rigorous standards for when dignity applies? Will it abandon dignity language altogether in favor of more traditional doctrinal tests? Or will dignity continue its shape-shifting journey through American jurisprudence?

What’s certain is that dignity cases offer some of the most compelling examples of how constitutional law evolves—sometimes coherently, sometimes contradictorily, but always in response to changing social understandings of what it means to be human in a free society.

The next time you see “dignity” in a Supreme Court opinion, ask yourself: Is this advancing a principled understanding of constitutional liberty, or is it just a prettier way of saying “because we said so”?

Doctrinal notes:

Dignity as a Constitutional Value Is Unstable - Casey used dignity to protect individual autonomy, but later cases (Gonzales v. Carhart, Dobbs) used dignity to justify restricting autonomy, showing how dignity arguments can be flipped to support opposite outcomes.

Impact on Rights Doctrine - Dignity reasoning fueled expansions of LGBTQ+ rights (Lawrence, Windsor, Obergefell), yet failed to secure abortion rights in Dobbs. This highlights how substantive due process arguments can be selective and dependent on judicial philosophy rather than consistent rules.

What do you think? Is dignity a meaningful constitutional principle or judicial camouflage?

Regarding Roe and the Court's decision to overturn it in Dobbs, I think this issue turns on how broadly or narrowly one construes the right. In reading the opinions of conservative justices in Roe and Dobbs, they narrowly frame the right as the right to an abortion and whether this is constitutionally protected. However, the liberal justices tend to frame it as a broader right of reproductive choice. I find myself agreeing with the latter formulation that the liberty involved in these cases isn't strictly the liberty/right to get an abortion but rather the liberty/right to make choices for oneself, including whether one wants to be a parent (or if they do, how they want to raise/parent the child). People have the capacity to make decisions for themselves regarding the trajectory of their own lives, and we trust that each person will make the decision that's best for themselves. To not adhere to this would be to encourage the development of an overly-paternalistic government.

I am reminded from cases like Faretta v. California, where the Supreme Court decided that criminal defendants have a constitutional right to represent themselves and forgo the assistance of counsel. The Court stated that forcing a person to be represented by council would be the equivalent of imprisoning them in a box of their constitutional rights. The same way that the state cannot force you to forgo parenthood, it should also not be able to force a person into parenthood or carrying a pregnancy to term.

Additionally, we trust that parents will also make the best decisions they can for their children. That is why parents have the freedom to enroll in their kids in public, private, or homeschool. Parents who homeschool have freedom in determining what the child will learn. Similarly, I think there is an argument to be made that an impoverished woman who struggles to afford her own cost of living is making the best possible decision for the potential human life when she receives an abortion because it spares the fetus from the harsh conditions and negative health outcomes associated with poverty.

I think dignity is a meaningful constitutional principle when it is used in a consistent way to protect individual autonomy and identity defining choices, but without clear standards it can be considered judicial camouflage - working as an abstract label to mask rulings considered subjective. This just leaves me wondering how dignity can mean one thing in one case and the complete opposite in another.