35. The Two Meanings of Brown v. Board

And why they still shape the fight over racial justice today

It begins with a feeling.

A little Black girl, six years old, walks past the all-white school every day on her way to the underfunded one she’s allowed to attend. The white school is closer. Bigger. Brighter. She doesn’t have the words for it yet, but she already understands the message: You don’t belong.

When the NAACP lawyers selected cases like hers to challenge segregation, they weren’t just arguing about distance or textbooks. They were arguing about dignity. About what the law teaches children when it draws a line and says, you on this side, you on that.

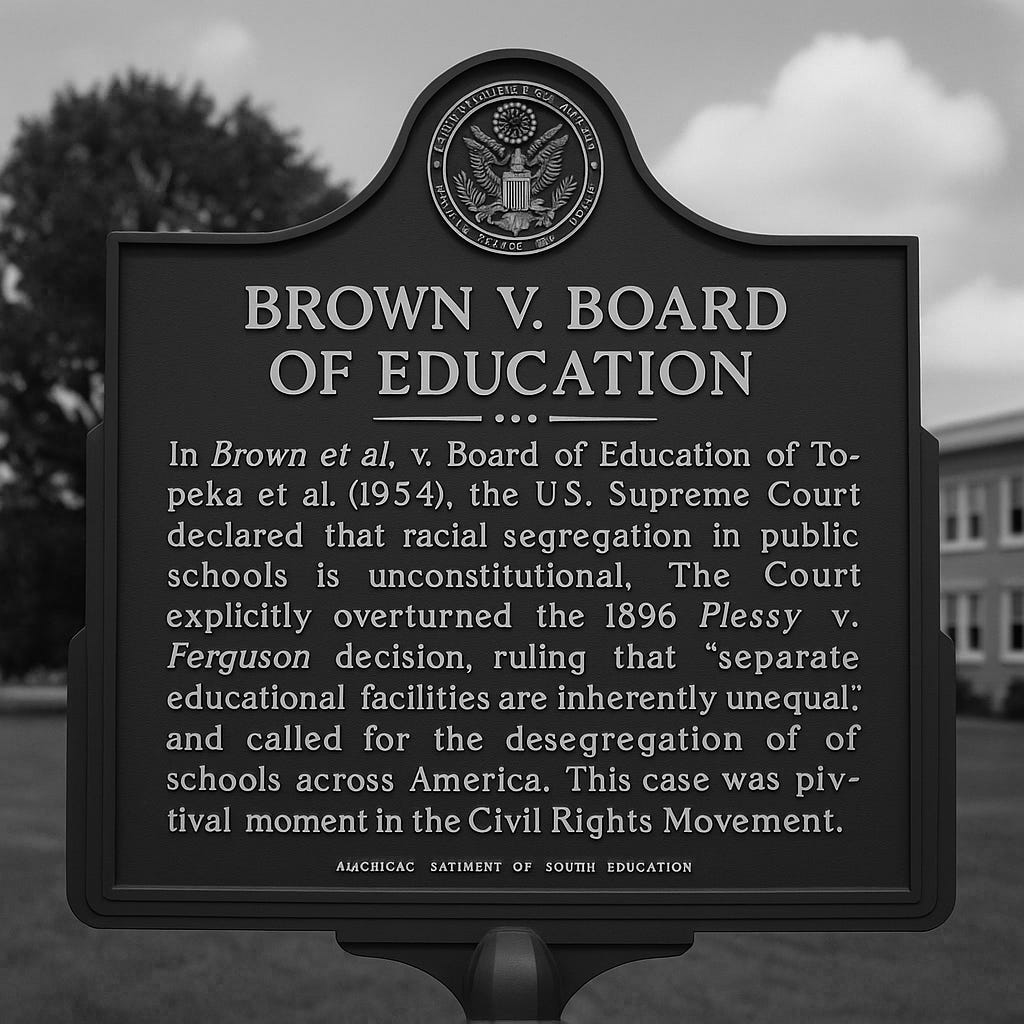

In 1954, the Supreme Court finally responded. In Brown v. Board of Education, Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote that segregation “generates a feeling of inferiority … that may affect the hearts and minds of Black children in a way unlikely ever to be undone.” Separate was not equal, not because the buildings or books were different, but because separation itself was a tool of subordination.

But even as Brown marked a legal and moral breakthrough, its meaning was already contested.

And over the decades that followed, courts, scholars, and activists would interpret Brown in starkly different ways, some seeing it as a mandate to dismantle white supremacy, others reading it as a ban on all race-conscious action, even that meant to heal. These interpretations would guide, and sometimes constrain, the nation’s efforts to pursue racial justice.

Two Theories of Equality: Anticlassification vs. Antisubordination

In her landmark article “Equality Talk,” legal scholar Reva Siegel explains that debates over Brown are really debates over what equality means.

The anticlassification theory sees Brown as standing for the idea that government must not classify individuals by race. Racial classifications, whether they hurt or help minorities, are inherently suspect. This is the “colorblind Constitution” view.

The antisubordination theory, by contrast, sees Brown as a rejection of systems of racial hierarchy. Under this view, racial distinctions are unconstitutional not because they name race, but because they entrench the political, social, and economic dominance of one group over another.

These theories may sound abstract. But they lead to wildly different answers when it comes to modern questions: affirmative action, school integration, even voting rights.

What Did Brown Actually Say?

On paper, Brown seems to lean antisubordination. The Court didn’t say segregation was unconstitutional because it made racial classifications. It said it was unconstitutional because it marked Black children as inferior. Because it upheld a caste system.

To support this claim, the Court pointed not to legal precedent, but to psychology.

The decision famously cited the Clark doll experiments, a set of studies conducted by psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark in the 1940s. In these experiments, Black children were shown two dolls—identical except for skin color—and asked which doll was “nice,” “pretty,” or “bad.” A striking majority of children attributed positive traits to the white doll and negative ones to the Black doll. Many preferred the white doll overall.

The Clarks concluded that segregation had inflicted psychological harm: it had taught Black children to see themselves as inferior.

By invoking these studies, the Court argued that separate schools weren’t just unequal in resources, they were damaging to the soul. Segregation wasn’t just separating bodies; it was shaping minds.

But there’s a tension.

Warren’s opinion avoids naming white supremacy or historical subjugation directly. It never explains why segregation harms students except by relying on social science. It was a moral argument masked as empirical fact.

And that’s where critics pounced.

The Critiques: Is Brown Too Soft?

In 1959, legal scholar Herbert Wechsler argued that Brown failed to articulate a neutral principle. If racial separation is wrong because it harms one group’s feelings, does that mean it’s okay if the feelings change? Shouldn’t the Court have grounded its ruling in a firmer legal doctrine, like freedom from state coercion?

Siegel’s response to these critiques is powerful. She argues that this demand for neutrality—this insistence on “colorblind” reasoning—is itself not neutral. It’s a political choice that favors the status quo. By avoiding the reality of racial subordination, anticlassification theory lets courts strike down race-conscious remedies (like affirmative action) while leaving historic structures of inequality untouched.

In other words: the law becomes a shield for white comfort rather than a tool for racial justice.

How the Meaning of Brown Shifted

In the years immediately following Brown, courts used its principles to strike down segregation in other public spaces: buses, beaches, parks, even golf courses. Civil rights activists read Brown as a license to push forward—not just for integration, but for systemic change.

But by the 1970s and beyond, the momentum slowed. A new generation of judges and justices began reading Brown differently. Not as a mandate to rectify racial harm, but as a rule against noticing race at all.

This narrowing reached a peak in the early 2000s.

In Parents Involved v. Seattle School District No. 1 (2007), the Court struck down voluntary integration plans. Chief Justice Roberts famously wrote:

“The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.”

Justice Thomas went further, arguing that Black students had succeeded in segregated schools, so integration wasn’t necessary for learning. The problem, he suggested, wasn’t separation, but interference.

But under Siegel’s antisubordination lens, this logic misses the point entirely. Brown wasn’t just about mixing students by race. It was about rejecting a systematic message of inferiority, a message encoded in the law, in funding structures, in district lines, in school closures. When the Court now uses Brown to strike down efforts to remedy that legacy, it turns a decision about dismantling caste into one that enforces formal symmetry.

Why It Matters Now

Siegel’s framework gives us language for the debates we’re still having:

Should the Constitution prohibit all racial classifications, even if they’re meant to promote equity?

Is a race-conscious policy inherently discriminatory—or does it matter who is classifying whom, and why?

Can courts claim neutrality while ignoring structural racism?

And perhaps most urgently:

If we read Brown only through the lens of classification, do we lose its power to challenge subordination?

Final Thoughts: A Legacy at Risk

The little girl walking past the white school didn’t need sociology to tell her what segregation meant. She felt it in her bones. Brown gave her hope that the law might finally see what she saw.

But if we forget what Brown was really about—if we reduce it to a rule against naming race—we risk turning that hope into betrayal.

The fight over the meaning of Brown is the fight over the meaning of equality itself.

And Reva Siegel helps us see that not all “equality talk” is created equal.

I think it does matter who is classifying whom and why. What is frustrating about the way these opinions read, from Brown v. Board to the other cases we’ve read prior on classification and equal protection, is that there’s this underlying assertion that addressing race or sex or sexuality creates an immediate uneven playing field. These opinions (the excerpts we’ve read) include such a surface level account of history in a way that minimizes and often just completely ignores that harm that’s been done and the generations of time that would have to pass WITH actions in equity that could classify as “reparative”. The idea that classifying race or sex (insert protected class here) in an action meant to promote equity is discriminatory is laughable to me. If discriminatory “describes actions or practices that show unfair, prejudicial treatment of people or groups based on characteristics like race, gender, age, religion, or sexual orientation. It implies unequal treatment due to biases against particular classes or categories of people”, then perhaps the operative word to be focusing on is “unfair”. Frankly, there have been such evils enacted from the beginning of the nation’s founding to the present day that we continue to witness and suffer the reverberations of those policies and laws, and I am not convinced that actions taken in pursuit of equity is in some way replicative of that same evil. I think it’s an excuse to maintain subordination and the existing caste system.