10. The Woman Who Opened Pandora’s Box

And why we’re still arguing about shadows sixty years later

Estelle Griswold had no idea she was about to unleash one of the most contested ideas in American constitutional law. All she wanted to do was help married couples in Connecticut get birth control.

It was 1961, and Connecticut had one of the most ridiculous laws on the books: the Comstock Act banned contraceptives entirely. Not just selling them—using them. Even married couples couldn’t legally use birth control in the privacy of their own bedrooms.

Griswold, the executive director of Planned Parenthood of Connecticut, decided enough was enough. She opened a clinic in New Haven, handed out contraceptives and advice, and waited to get arrested.

She didn’t wait long.

The Case That Created Constitutional Shadows

When Griswold v. Connecticut reached the Supreme Court in 1965, something strange happened. Seven justices agreed the Connecticut law had to go—but they couldn’t agree on why.

Justice William Douglas, writing for the majority, came up with what might be the most poetic (and criticized) metaphor in constitutional law: penumbras.

Stick with me here.

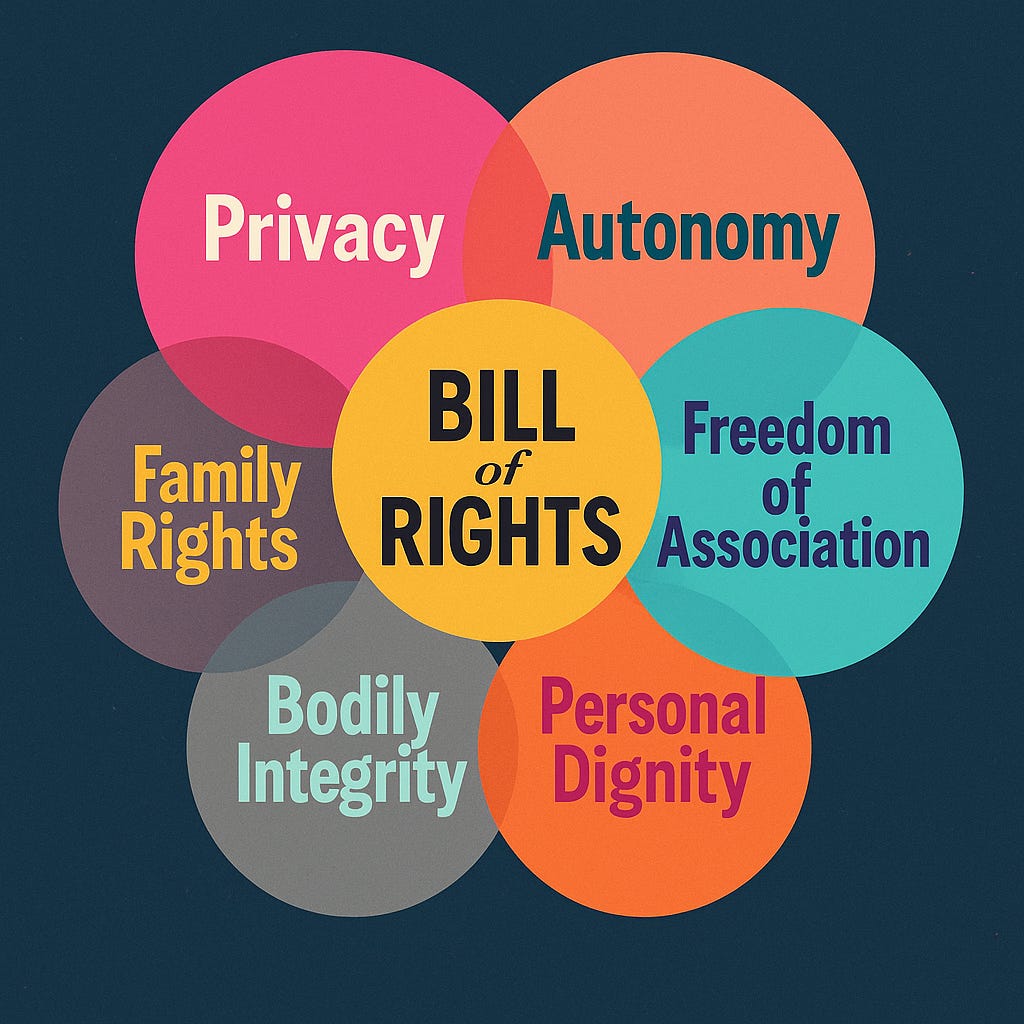

Douglas argued that even though the Constitution doesn’t contain the word “privacy,” several of its explicit protections work together to create a private sphere the government shouldn’t invade.

He chose examples that all had something in common: they shield people from government intrusion into their personal lives and private spaces. The First Amendment protects the right to freely associate with others. The Third bars soldiers from being quartered in people’s homes. The Fourth guards against unreasonable searches and seizures. The Fifth lets individuals remain silent rather than testify against themselves. And the Ninth acknowledges that the people have rights beyond those specifically listed in the Constitution.

Marriage, Douglas declared, sits at the heart of this shadowy zone.

It was brilliant legal poetry. It was also a constitutional Rorschach test that we’re still arguing about today.

Four Theories for One Result

Griswold is one of those cases where the Court reached a clear result but not a clear rationale. Even the justices in the majority couldn’t quite agree on how to get there.

· Justice Douglas: Zones of privacy arise from the “penumbras” cast by several constitutional rights.

· Justice Goldberg: The Ninth Amendment protects unenumerated rights like marital privacy.

· Justice Harlan: The Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause protects fundamental liberties rooted in history and tradition.

· Justice White: The Connecticut law was irrational and couldn’t survive even minimal scrutiny.

Meanwhile, the dissenters pushed back hard.

· Justice Hugo Black called the majority’s reasoning a judicial overreach: “I like my privacy as well as the next one,” he wrote, “but I am nevertheless compelled to admit that government has a right to invade it unless prohibited by some specific constitutional provision.”

· Justice Potter Stewart was even blunter, calling Connecticut’s law “uncommonly silly” but insisting there was no constitutional basis to strike it down.

A Conservative Revolution

Here’s the paradox: Griswold broke new ground in constitutional interpretation, but it did so in the service of a deeply traditional ideal—marriage.

Douglas didn’t frame the case in terms of sexual freedom or women’s autonomy. He described marriage as “a relationship lying within the zone of privacy created by several fundamental constitutional guarantees,” and spoke of it as “intimate to the degree of being sacred.”

In other words, this wasn’t about free love or a broader right to make intimate choices—it was about shielding the sanctity of the marital bedroom from government intrusion.

That narrow framing mattered. Griswold only protected married couples. Unmarried people were still subject to contraception bans. It wasn’t until Eisenstadt v. Baird (1972) that the Court extended contraception rights to individuals regardless of marital status—this time emphasizing personal autonomy: “If the right of privacy means anything, it is the right of the individual, married or single, to be free from unwarranted governmental intrusion into matters so fundamentally affecting a person as the decision whether to bear or beget a child.”

Who Was Really Being Protected?

As with many landmark cases, the sanitized facts don’t tell the whole story. Griswold was framed as protecting respectable, middle-class married couples. But in practice, Connecticut’s contraception ban disproportionately affected poor women—often immigrants and working-class families—who relied on birth control clinics like Griswold’s.

Wealthier couples could quietly obtain contraceptives from sympathetic doctors or simply travel to New York. It was vulnerable women, with fewer options, who faced the harshest consequences of the law.

It’s worth noting that the law’s strongest political support came from the Catholic Church, which viewed contraception bans as aligned with its moral teachings. The result was a law shaped by a particular religious perspective, rather than by neutral public health considerations.

The Constitution creates a private sphere the government shouldn’t invade.

The Penumbra Problem

Douglas’s “penumbra” theory was controversial from the start. If judges can combine various constitutional guarantees to infer new rights, where should they draw the line? What prevents them from reading their own preferences into the Constitution?

Critics argue that Douglas’s approach lacked clear limits and invited judicial activism. But defenders point out that refusing to recognize implied rights can be just as activist—in effect allowing government intrusions the Framers never intended. After all, the Constitution’s text and structure suggest that personal liberty encompasses more than just what’s explicitly listed.

There’s no truly “neutral” answer here. Every interpretive approach reflects a theory about the Constitution’s meaning and how courts should read it.

Still Arguing About Shadows

Sixty years after Estelle Griswold opened her clinic, we’re still wrestling with the questions her case raised.

Should courts protect implied rights when the Constitution’s structure suggests them? Or should they stick narrowly to rights explicitly listed or deeply rooted in history?

Today’s debates over privacy, bodily autonomy, and personal freedom all trace back to that fateful moment when Douglas looked at the Bill of Rights and saw not just isolated clauses, but overlapping protections that together shield our most intimate decisions.

Estelle Griswold just wanted to help married couples plan their families. In doing so, she opened a constitutional Pandora’s box that we’re still debating today.

Doctrinal take-away:

Right to Privacy Introduced - even though not textually stated.

Marriage-Centric Framing - privacy tied to sanctity of marriage, not individual autonomy

Penumbra Debate - sparked ongoing debate about “judicial activism” vs. “faithful interpretation” (Lochner started that conversation focused on economics; Griswold shifted that debate to personal rights and privacy).

Legacy - foundation for reproductive autonomy cases (e.g., Roe v. Wade); precedent for broader autonomy rights (e.g., sexual intimacy, same-sex marriage).

When Roe v. Wade was overturned, it stoked fears in some Americans that this could be a stepping stone to overruling the right to gay marriage as well, or the right to use contraception, or the right to not be sterilized. How will Dobbs affect these wide-ranging cases that also have to do with privacy? What are its ripple effects on Douglas’s ideas about penumbras?

I know that some countries explicitly state both privacy and personal autonomy within their constitutional frameworks, resulting in a sense of clearer guidance for their courts. Germany, for example, grounds many individual rights in the inherent dignity of the person, which serves as a strong foundation for protecting both reproductive freedom and bodily autonomy. So, I find that this contrasts deeply with the US approach within Griswold, where these rights had to be inferred through "penumbras" of other guarantees. Could these more direct legal models help create a more consistent or democratic alternative to the uncertainty the US still debates today, or do you think an application of this kind is impossible in today day and age?