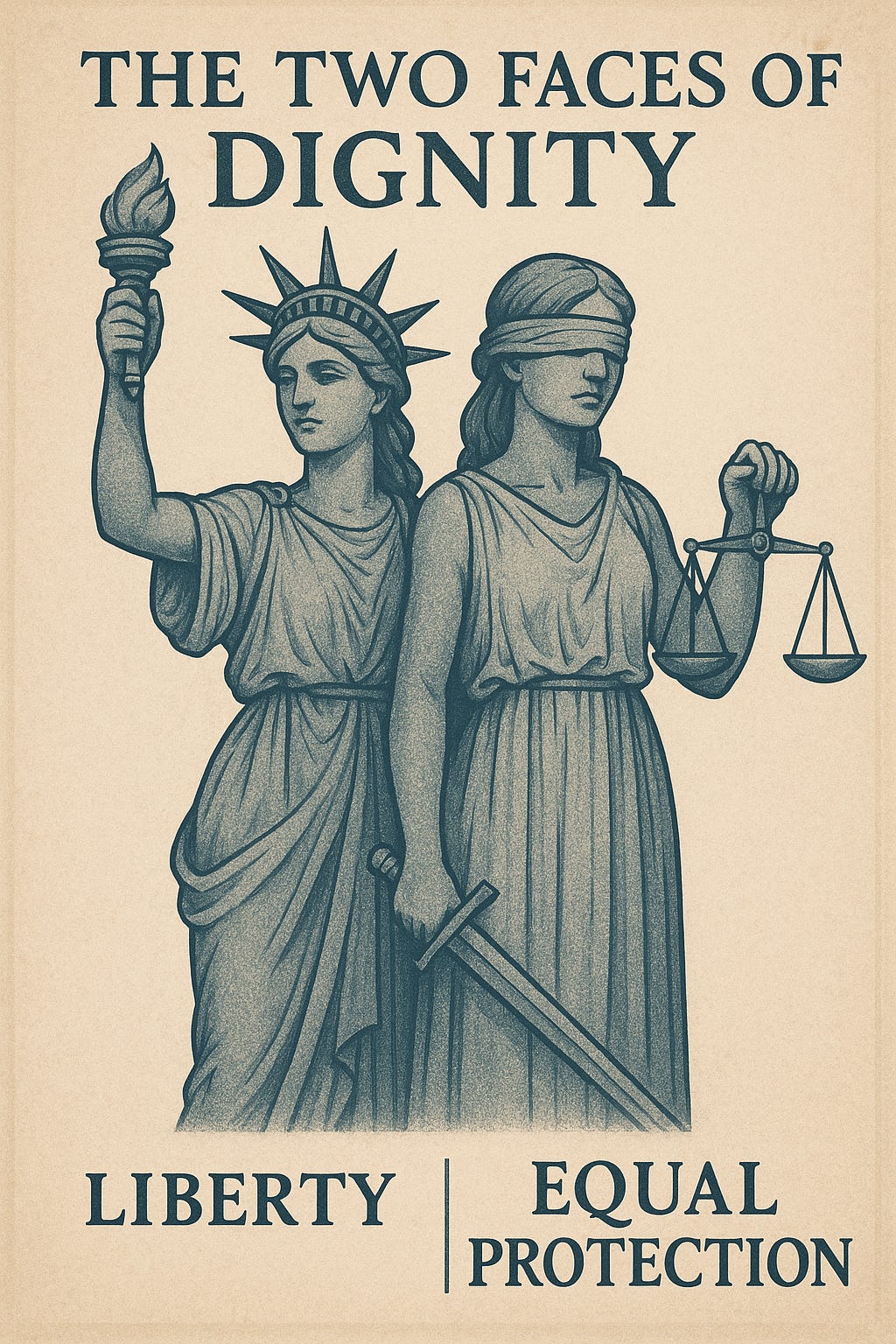

25. Two Faces of Dignity

Lawrence, Windsor, and the constitutional self

In constitutional law, the word dignity carries a strange kind of weight. It appears often (especially in Justice Kennedy’s opinions) but always slightly out of reach, like light refracting through water. It gestures toward something fundamental, even sacred, but resists precise definition.

Two landmark cases—Lawrence v. Texas (2003) and United States v. Windsor (2013)—offer an opportunity to trace the contours of this elusive concept. Both invoke dignity. But they do so in strikingly different ways.

In Lawrence, dignity means liberty.

Lawrence struck down Texas’s sodomy law, which criminalized private, consensual sexual conduct between adults of the same sex. The case wasn’t about marriage or benefits or official recognition. It was about the state’s intrusion into the most intimate corners of personal life. The government, Justice Kennedy wrote, “cannot demean their existence or control their destiny by making their private sexual conduct a crime.”

Here, dignity is about freedom from moral disapproval. It’s not conferred by the state; it’s already yours. It arises from autonomy, the idea that your body, your desires, your private relationships belong to you alone. No law, no state, no majority opinion should be allowed to reach inside that space. This is dignity as negative liberty—the right to be left alone.

In Windsor, dignity means recognition.

Ten years later, Windsor addressed a very different harm. Edith Windsor had legally married her partner, Thea Spyer, in Canada. New York recognized the marriage. But the federal government did not, thanks to the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which defined marriage as between a man and a woman for federal purposes.

When Thea died, Edith was hit with a $363,000 tax bill, money she wouldn’t have owed if her spouse had been recognized under federal law. The real injury, though, wasn’t just financial. It was existential.

Justice Kennedy again invoked dignity, but this time, it was relational. DOMA, he wrote, “places same-sex couples in an unstable position of being in a second-tier marriage. The differentiation demeans the couple, whose moral and sexual choices the Constitution protects.” It also “humiliates tens of thousands of children” by telling them their family is less worthy than others.

Here, dignity isn’t about autonomy. It’s about status. It’s about being seen by the state. It’s about equality under law. This is dignity as public validation (think of it as positive liberty): the right to have your relationships and identity recognized as fully human, fully legitimate.

Can both ideas be true?

At first glance, these two versions of dignity might seem to pull in opposite directions. One says the state should back off. The other says the state should step up.

But they’re not opposites. They’re complements.

The dignity at the heart of Lawrence is personal—it guards the interior space where identity is formed, relationships are chosen, and autonomy is exercised. The dignity at the heart of Windsor is institutional—it reflects how the law either affirms or denies your place in the social and legal order.

Taken together, these cases suggest a richer view of the constitutional self: not just as a private actor free from interference, but as a public equal worthy of recognition.

This duality matters. It reminds us that harm can take many forms. Sometimes it’s the state barging in where it doesn’t belong. Sometimes it’s the state’s silence, its refusal to name or honor your existence.

Both can wound. And both can be remedied when we remember that dignity isn’t one thing. It’s a bridge between liberty and equality. Between the self and society.

Doctrinal take-away:

Two forms of constitutional dignity emerge in LGBTQ+ cases:

Lawrence v. Texas (2003) → dignity as negative liberty: protection from state intrusion into private, intimate life.

United States v. Windsor (2013) → dignity as public recognition: equal status and validation of legally recognized relationships.

Together, these cases show dignity as a bridge between liberty and equality—protecting both personal autonomy and social/legal recognition as fundamental to constitutional personhood.

When you think of dignity in your own life, does it feel more like freedom from judgment—or the longing to be fully seen?