34. When the Law Looked Away

Race, segregation, and the Fourteenth Amendment’s broken promise

In the last two posts, we looked at how the Fourteenth Amendment was born in conflict and how one long-dormant clause—the Privileges or Immunities Clause—was quietly revived to protect national citizenship and the right to travel. But that’s only one part of the story.

The Fourteenth Amendment was supposed to transform the legal status of Black Americans, ensuring that states could no longer trap them in a second-class existence. But when the Supreme Court had the chance to enforce that promise in its early cases, it blinked.

Worse—it helped build the legal foundation for Jim Crow.

Early Hopes: Jury Service and Strauder v. West Virginia (1880)

One of the first signs of progress came in Strauder, where the Court struck down a law allowing only white men to serve on juries. The justices recognized that excluding Black citizens from such a fundamental civic role violated the Equal Protection Clause.

It was a meaningful decision—but narrow. Jury service was protected. Segregated schools, segregated transit, segregated public spaces? The Court stayed silent.

A Step Back: The Civil Rights Cases (1883)

Congress had tried to go further, passing civil rights laws that banned racial discrimination in hotels, theaters, and other public businesses. The idea was simple: if you serve the public, you should serve everyone.

But the Court disagreed. In The Civil Rights Cases, it held that the Fourteenth Amendment only applied to state actions, not to private businesses. The result?

States couldn’t discriminate, but private citizens and businesses could.

This ruling stripped the federal government of the power to stop racial exclusion in public life. Discrimination became legal by default. It was a devastating blow that helped entrench segregation in housing, transportation, and employment for generations.

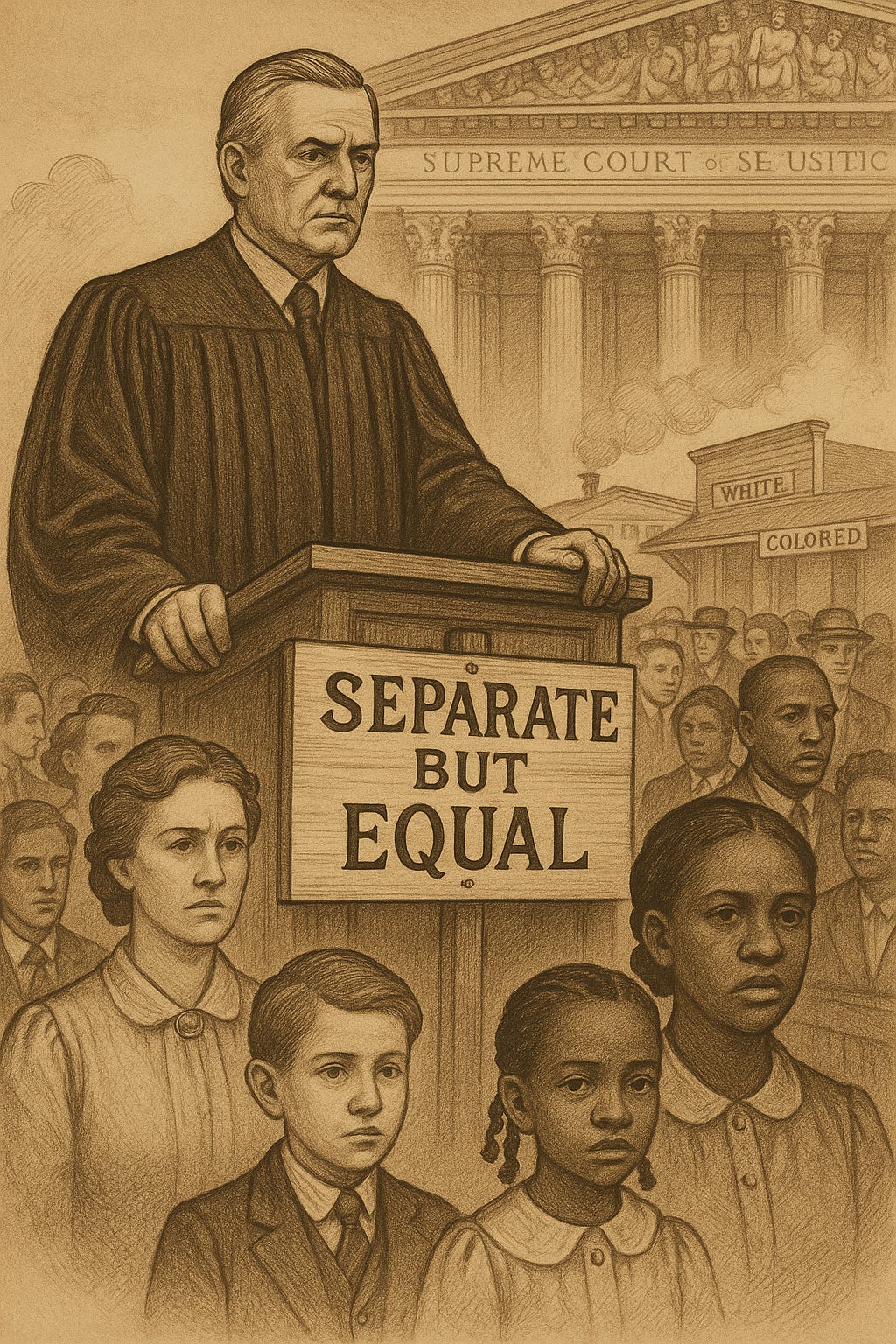

“Separate But Equal”: Plessy v. Ferguson (1896)

By the 1890s, Southern states had taken the Court’s hands-off approach and run with it, legally enforcing separation of Black and white citizens in nearly every aspect of life.

When Homer Plessy challenged Louisiana’s segregated train cars under the Equal Protection Clause, the Supreme Court shut him down. Justice Henry Billings Brown wrote the now-infamous phrase:

“Separate but equal.”

The Court claimed the law didn’t make Black citizens inferior—only they felt that way. It framed segregation as neutral. But as we know: separate was never equal.

Black schools, train cars, and neighborhoods were almost always worse in funding, infrastructure, and opportunity. But with Plessy, the Court gave Jim Crow laws a constitutional green light.

The One Dissent: Justice Harlan

Justice John Marshall Harlan dissented powerfully in Plessy. He declared:

“Our Constitution is colorblind.”

He saw what the majority refused to admit: that segregation wasn’t neutral, it was designed to enforce racial hierarchy. Harlan’s dissent is remembered today as prophetic.

But even he had limits: he supported the exclusion of Chinese immigrants and echoed the racism of his era in other ways. His dissent is a reminder that even the most forward-thinking voices of the time were still shaped by deeply embedded biases.

Fighting Back: The NAACP and the Legal Attack on Plessy

In the decades after Plessy, the NAACP began building a legal strategy to dismantle segregation piece by piece. Instead of attacking Plessy head-on, they targeted its weakest link: the idea that separate schools could ever be equal.

They started with graduate and law schools, where disparities were especially obvious. The cases they brought changed the conversation:

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada (1938): Missouri couldn’t just pay a Black student to go out of state. It had to provide a truly equal school in-state.

Sipuel v. Board of Regents (1948): Oklahoma couldn’t pretend a hastily-built, under-resourced law school was equal.

Sweatt v. Painter (1950): Even if facilities looked similar on paper, things like networking, reputation, and faculty access mattered to a student’s education and career impact, and these weren’t truly equal in Black schools.

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents (1950): A Black student was admitted to the University of Oklahoma’s graduate education program because a court had ordered it. But once enrolled, the university physically separated him from white students (he had to sit in the hallway during class, had a designated table in the cafeteria, and a separate desk in the library). The Supreme Court ruled that this kind of enforced isolation made true equality impossible.

Together, these cases chipped away at the legal fictions upholding segregation.

The Long Arc Toward Brown v. Board

By 1954, the groundwork had been laid. In Brown v. Board of Education, the Court finally admitted what everyone already knew:

“Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

It was the beginning of the end for legal segregation. But the victory came nearly 90 years after the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified—and only after generations of damage.

Final Thoughts: Law Is Not Neutral

If the Supreme Court had ruled differently in The Civil Rights Cases or Plessy, American history might have unfolded differently. The Fourteenth Amendment gave us the tools to build a racially just democracy—but for decades, the Court refused to use them.

These cases remind us that law isn’t just about what the Constitution says—it’s about who decides to enforce it, and for whom.

Legality is not the same as justice.

Constitutional text is not the same as constitutional power.

We live with the consequences of those early refusals. And the fight to close the gap between what the law promises and what it delivers is still ongoing.

On Harlan's Dissent.

I write now to clarify comments I made in class (and to get participation points for engaging with the Substack). Specifically, I pose the question: is the language in Harlan's dissent that has been widely criticized as racially problematic in truth a more sophisticated recognition of the systematic inequality inevitably ushered in by the institution of slavery?

That is, of course, an open question. It cannot be ignored that, as a white justice in 1896, Harlan's conception of racial equality was far removed from the modern conception of racial equality. Indeed, in the very same opinion in which Harlan advocates for the equality of Black Americans, he indicates that Chinese individuals should be absolutely excluded from consideration of citizenship. Throughout his career, he proceeded to endorse decisions which upheld exclusion of Chinese Immigrants. With that necessary disclaimer provided, I will turn to the language at issue. Specifically, Harlan wrote:

"The white race deems itself to be the dominant race in this country. And so it is, in prestige, achievements, in education, in wealth and power. So, I doubt not, it will continue to be for all time, if it remains true to its great heritage and holds fast to the principles of constitutional liberty. But in view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens." Plessy v. Ferguson (Harlan dissenting)

While facially controversial, In my view, this language speaks to the uncomfortable reality that the institution of slavery has created in the United States, the effects of which echo today. To begin, Harlan declares that the White race has "deemed itself" the "dominant race," "And so it is, in prestige, achievements, in education, in wealth and power." Surely this language is uncomfortable. However, it is not undue. Rather, this language speaks directly to a reality many attempt to ignore: by kidnapping individuals from Africa, subjugating them to slavery, denying them education, and categorically classifying slaves (or indeed, human beings) as property (See Dredd Scott), the White race had in no uncertain terms "deemed itself" the "dominant race."

However, the language of the dissent does not suggest that this dominance is intrinsically justifiable. Rather, Harlan's next sentence is inherently conditional: "So, I doubt not, it will continue to be for all time, if it remains true to its great heritage and holds fast to the principles of constitutional liberty." In other words, the White race's self manufactured domination will continue if. If what? If it does exactly what the Plessy majority endeavors to do. Specifically, if it continues to purport history, tradition, morality, and heritage justify the subjugation and dehumanization of a certain class of human beings.

In Harlan's view, the majority has veiled a "thing disguise of 'equal' accommodations" that will "not mislead any one, nor atone for the wrong this day done." Plessy v. Ferguson (Harlan dissenting). In no uncertain terms, Harlan admonished the majority for its interpretation, stating that "in view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens." The remainder of Harlan's dissent provides tangible substance to this statement. Indeed, Harlan stated he would "deny that any legislative body or judicial tribunal may have regard to the race of citizens when the civil rights of those citizens are involved," and likend the majority's opinion to that of the infamous Dredd Scott case.

I believe that a categorization of Harlan's language as stating that the White race will intrinsically remain a dominant class dilutes the substance of his writing. Within this paragraph, Harlan has vocalized that the White class has self-manufactured a certain "dominant race" and has disavowed the existence of a "dominant race" in precise terms. Accordingly, I believe that a more nuanced reading supports the conclusion that Harlan is an early acknowledger of a trend we have seen continue throughout American Jurisprudence. Certain members of the White class may attempt to use law, history and tradition, and structural inequality to cling tightly to a self-manufactured position of dominance.

I apologize for the formatting and citation challenges inherent to writing a discussion post.